This is a carousel. Use Next and Previous buttons to navigate

一个minuscule bug caused an ecological nightmare across Northern California nearly 40 years ago, and the fallout spread from the fields of Silicon Valley into the halls of the Capitol in Sacramento.

When searching The Chronicle’s archive, I came across a story about the Mediterranean fruit fly invasion of 1980-81. My interest piqued, I dug up more photos and articles about what became one of the strangest environmental events in Bay Area history: the mass spraying of pesticides over huge swaths of the South Bay, East Bay and the Peninsula.

The medfly’s Bay Area infestation was first announced July 8, 1980, after two adult males were found in a suburban San Jose backyard. The news had been deemed so sensitive by pest control specialists that the discovery was kept secret for two weeks as courses of action were discussed.

一个n article in The Chronicle the day after the announcement explained the risk: The pesky fly was known for attacking soft-skinned fruits and vegetables including apples, apricots, cherries, grapes, citrus and prunes — all of which were abundantly grown throughout Santa Clara Valley.

While agriculture had been a major economic enterprise for the county in the first half of the 20th century, suburban sprawl and the rise of Silicon Valley had led to a decline in farming. Still, farms were around and fears were elevated that the medfly could spread to the Central Valley and lay waste to what is now a $40 billion-a-year agriculture industry.

一个fter the flies were found, all fruit in Santa Clara County was quarantined, with shipments outside county borders banned. That was a $30 million hit to the local economy, but Chester Howe, the county’s agricultural commissioner, said, “It’s nothing compared to the $1 billion damage the medfly could cause statewide, if not eradicated now.”

豪解释攻击的计划:“我们计划to do is out-sex them, by releasing thousands of sterile males during the breeding season. ... The sterile males mate with the females and no fly eggs are produced.”

一个sexy plan indeed.

By late August, despite a $2 million eradication effort, more Mediterranean fruit flies were found outside the original 156-square-mile infestation area. State officials expanded the focus area to 450 square miles, encompassing all of Santa Clara Valley. Howe stated the obvious: “There’s no way we can stand at the border and swat them back.”

On Dec. 3, 1980, federal officials announced a plan to use the aerial spraying of insecticides in Alameda and Santa Clara counties. Immediately, a loose-knit coalition of groups opposed to the spraying held their own news conference, kicking off months of protests and legal actions, which would postpone spraying.

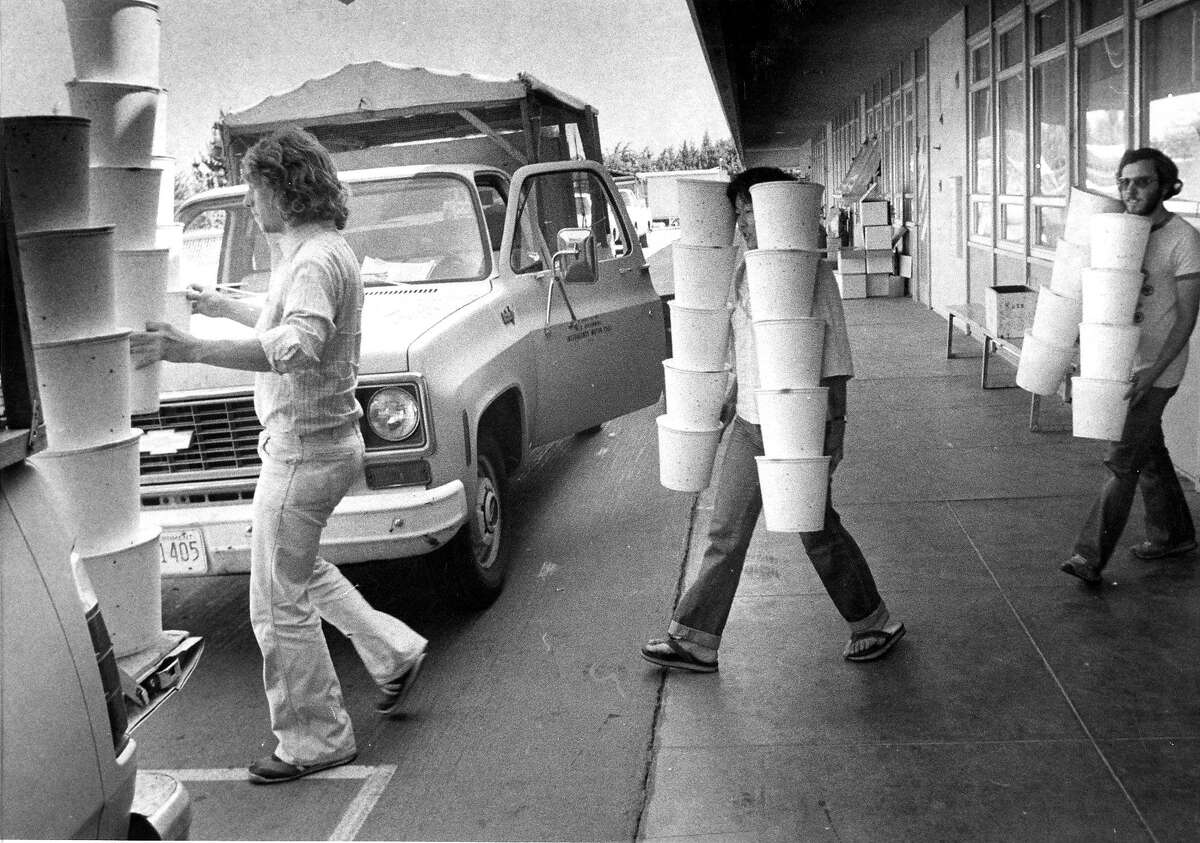

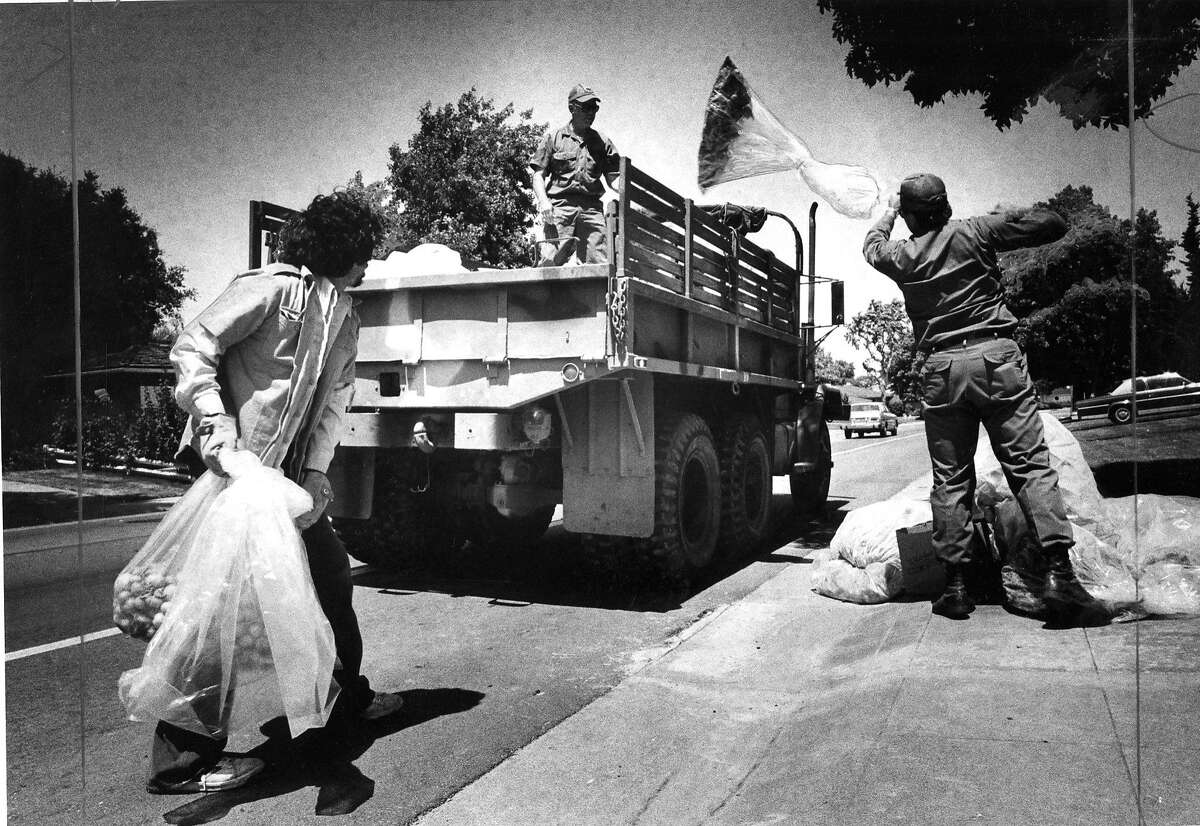

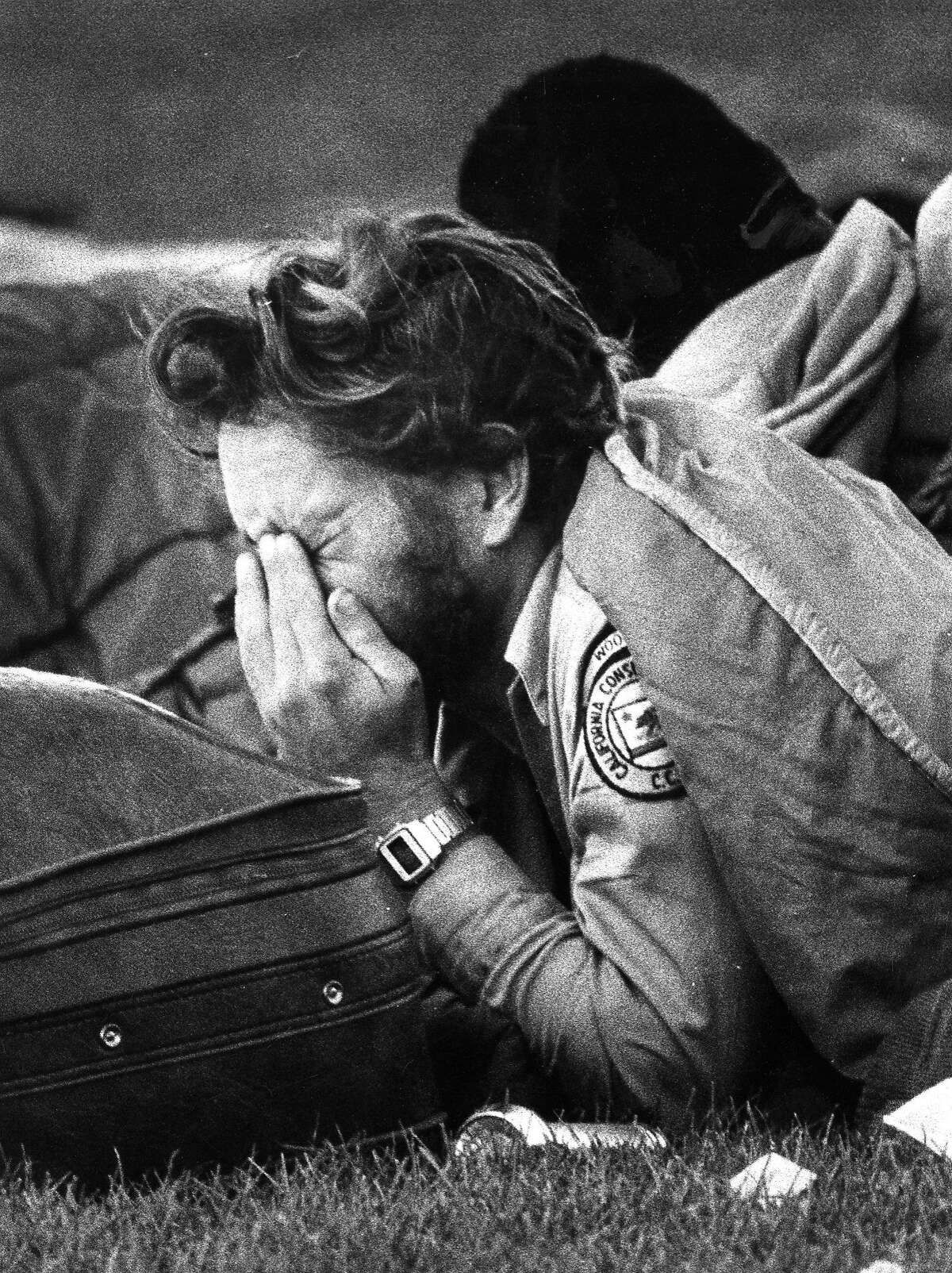

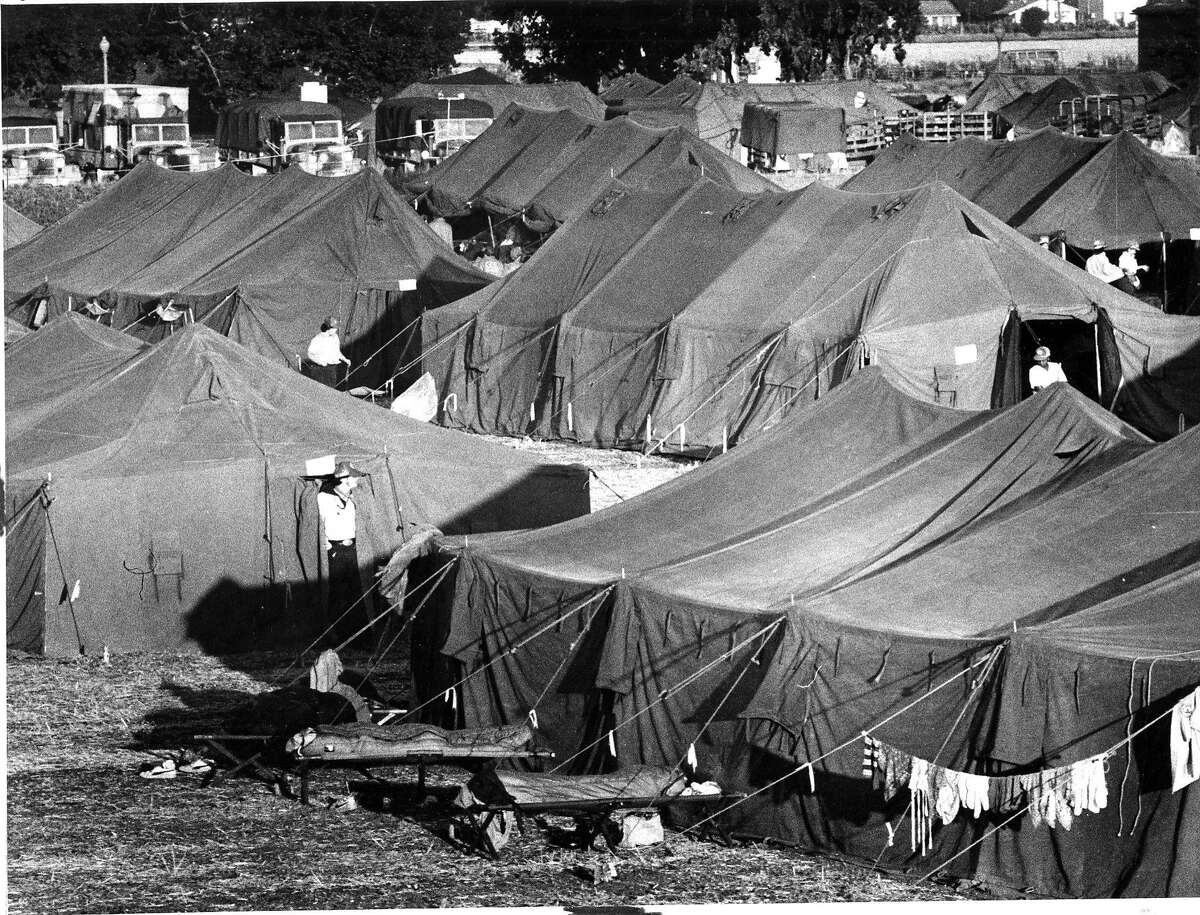

Meanwhile, nearly 1,000 California Conservation Corps members came to Santa Clara and Alameda counties to pick, collect and destroy all fruit found in nearby yards, ostensibly to stop the medflies’ spread. The National Guard joined in the fight as well.

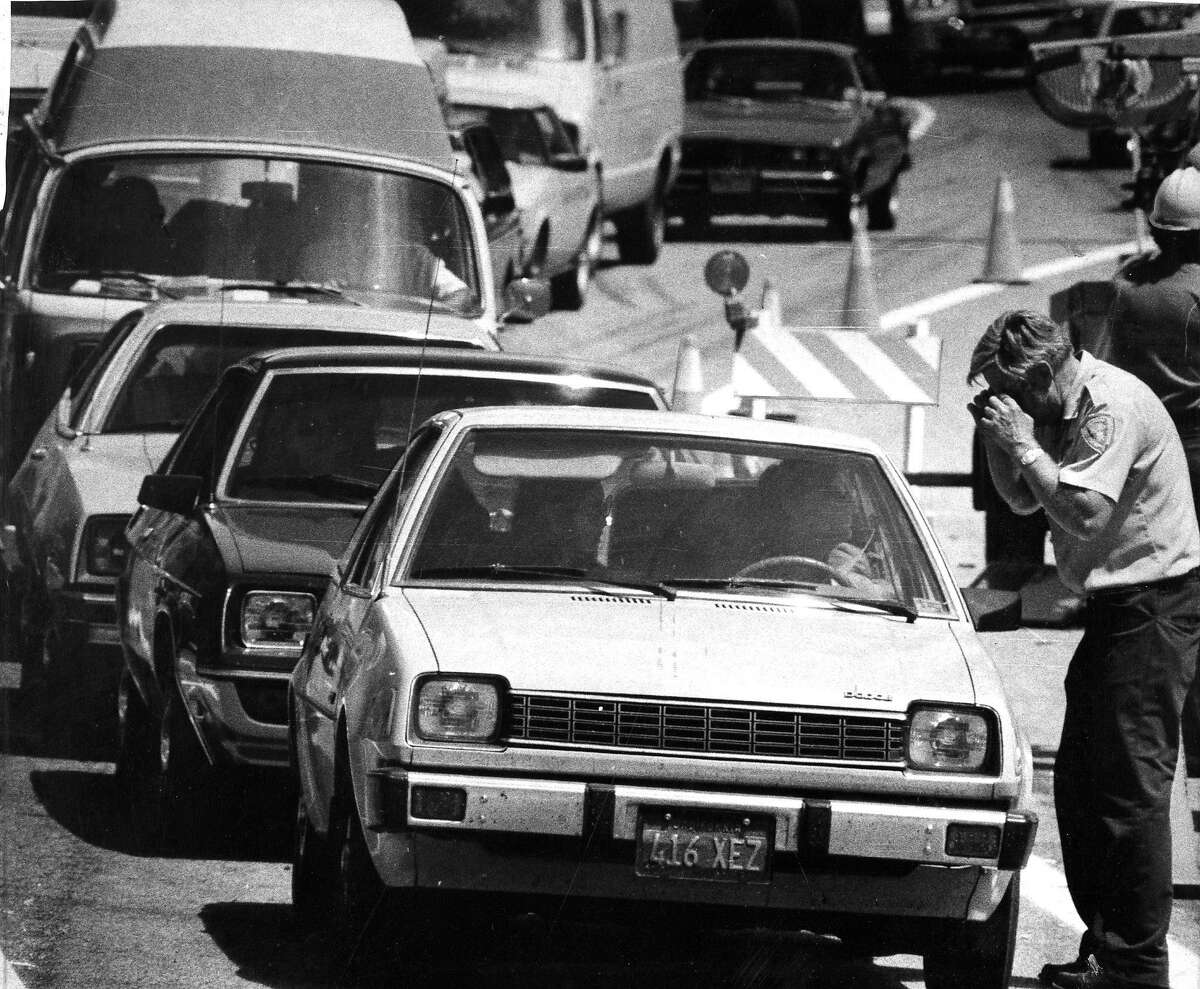

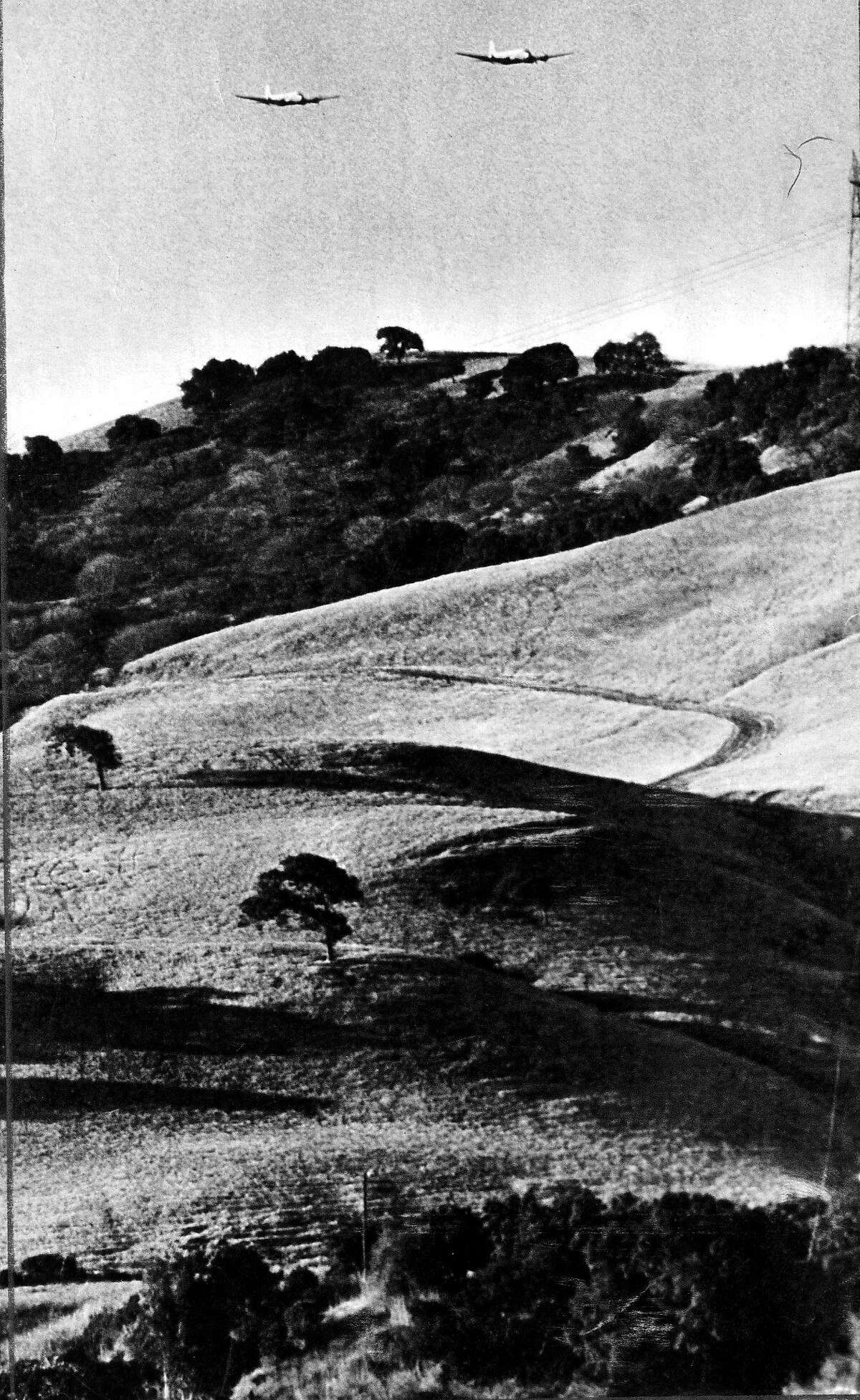

On July 11, 1981, bowing to threats of a federal quarantine of all California farm produce, Gov. Jerry Brown approved aerial spraying over a 97-square-mile swath of Santa Clara and Alameda counties. People were told to stay indoors and to keep pets inside.

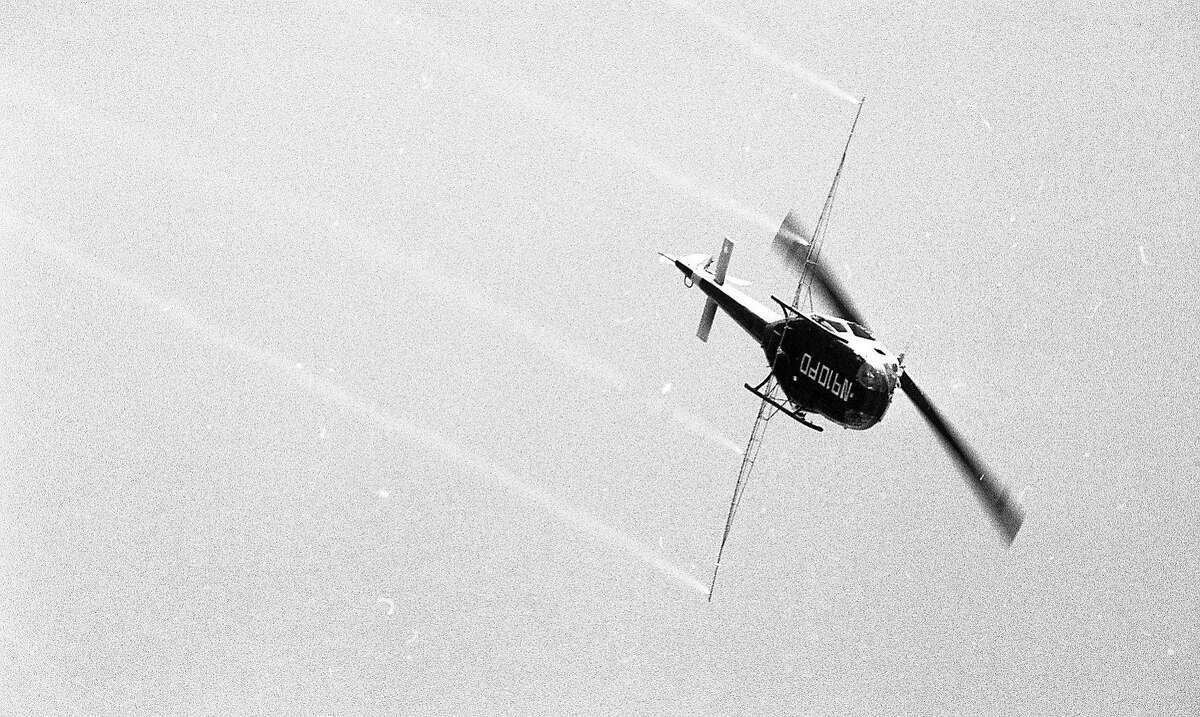

Hundreds of square miles were added to the spray zone over the coming year. By the next summer, the campaign had covered 1,400 square miles: an eight-county, 43-city area populated by 2 million residents. Squads of helicopters flew in formation, spraying seemingly indiscriminately over neighborhoods. The outrage was palpable.

On Sept. 21, 1982, after spending $100 million, the state declared victory over the medfly. The governor, though, suffered a political defeat in the aftermath of the environmental crisis when he lost a race for a Senate seat.

The medflies have returned to the region a few times over the decades, but these days they’re kept under control without aerial-spraying. Instead, millions of sterile flies are released year-round.

Bill Van Niekerken is the library director of The San Francisco Chronicle, where he has worked since 1985. In his weekly column, From the Archive, he explores the depths of The Chronicle’s vast photography archive in search of interesting historical tales related to the city by the bay.