This is a carousel. Use Next and Previous buttons to navigate

精英咖啡馆的霓虹灯依然hangs over San Francisco’s Fillmore Street, but the yellow lights, once beckoning people to gumbos made with roux the color of antique copper pennies and jambalaya served in golden heaps of rice and sausage, have gone dark.

Bayou closed last year, after a short run on Valencia Street. A few blocks away, Alba Ray’s recently discontinued dinner service and now only offers weekend brunch. Before that, Hayes Valley’s Boxing Room swapped its well-regarded Creole menu for Spanish fare; the Outer Sunset’s Cajun Pacific lasted 16 years before shutting down in late 2016. Even soul food stalwart Farmer Brown, a Tenderloin business with jambalaya and po’boys, closed in February after 13 years.

“If I had a chance to do it all again,” said Andrew Chun, the last owner of Elite Cafe, “I would have picked a different concept.”

Shifting demographics and an increasingly volatile industry have hit this category of restaurant especially hard. Diners are more health-conscious, and Cajun and Creole recipes based around butter, flour, salt and spice don’t always align with modern dining habits. The recipes take time to prepare, which means most Louisiana-inspired businesses are traditional sit-down concepts devoid of the increasingly popular counter-service touch.

Most of all, though, local chefs say they have a hard time meeting diners’ nostalgic expectations of what Louisiana cooking should be.

“My gumbo could be the best version they’ve ever had, and their original gumbo they remember could be s—, but if what I do doesn’t remind them of that, they get disappointed,” said Adam Rosenblum of Alba Ray’s.

Alba Ray’s makes Cajun food, the more blue-collar of the two styles of cuisine from Louisiana — focusing on fried catfish, spicy smoked sausage, shrimp and crawfish. Meanwhile, Creole food is more refined, and when it comes to jambalaya and gumbo, the recipes highlight seafood and include tomatoes.

The Bay Area has a deep history with both, one that can be traced back to the cuisine’s local proliferation during the Great Migration.

二战后,成千上万的非洲美国cans relocated to San Francisco from Louisiana and elsewhere in the South, pushing the city’s total black population to just under 5,000 by 1940. The population peaked by the 1970s at around 96,000. Families brought with them homespun recipes blending soul and Southern food with authentic Cajun and Creole tastes.

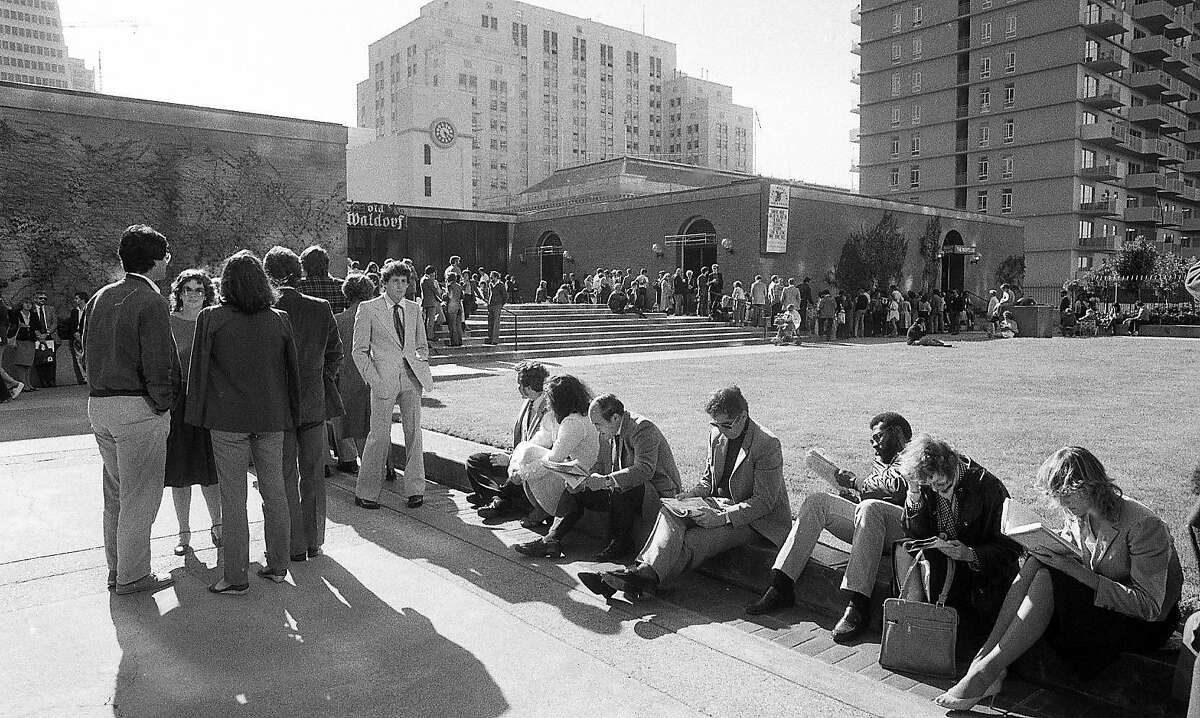

San Francisco’s infatuation with Louisiana food gained national attention during the summer of 1983. New Orleans celebrity chef Paul Prudhomme brought a pop-up version of his famed K-Paul’s Louisiana Kitchen to San Francisco’s Civic Center. Every night for a month, lines spilled through the door and into the neighborhood, toting wait times of three to six hours.

Alba Ray’s,2293 Mission St.,www.albarays.com

Brenda’s French Soul Food,652 Polk St.,www.frenchsoulfood.com

The Front Porch,65 29th St.,www.thefrontporchsf.com

Queen’s Louisiana Po-Boy Cafe,Pier 33,www.queenslapoboys.com

— J. P.

“In the mid-1990s when Emeril (Lagasse) was out there and K-Paul was doing those pop-ups, there was definitely an interest in Cajun and Creole food here,” said Joey Altman, a Bay Area chef who once worked under Lagasse at Commander’s Palace in New Orleans and is now the director of culinary operations at Pier 23 Restaurant. “It was the first time people out here were hearing of blackened fish and etouffee.”

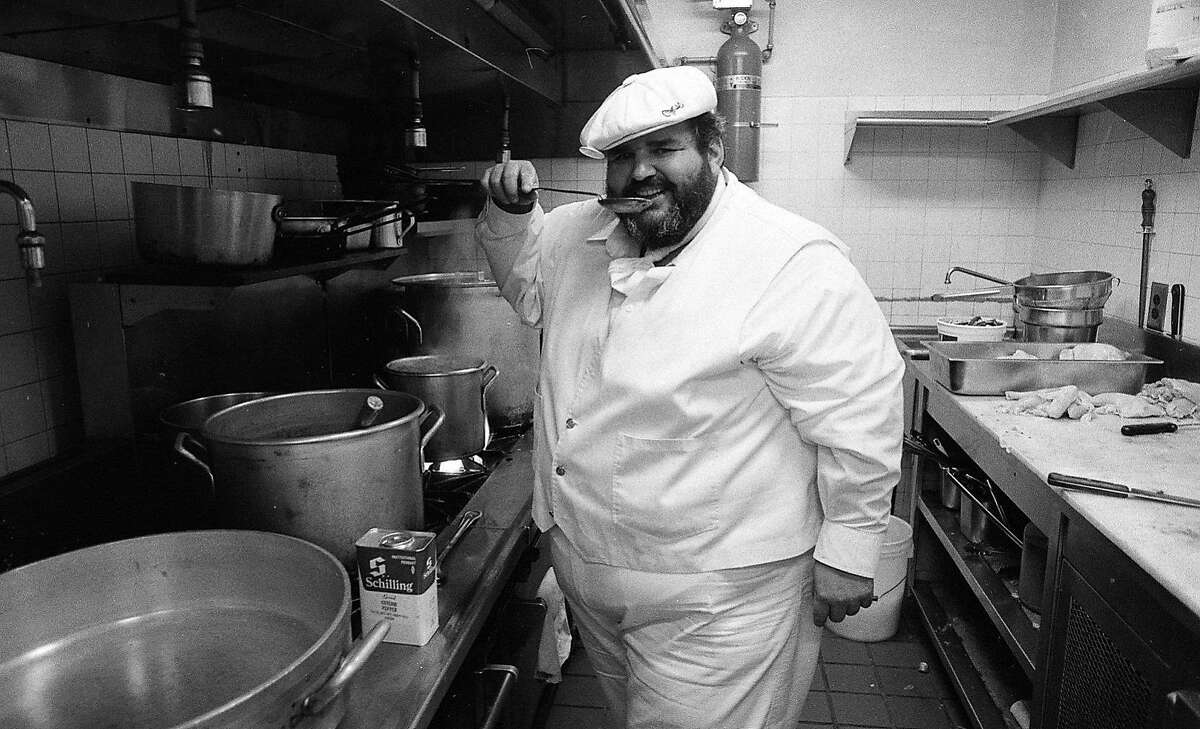

The popularity of the cuisine spurred a proliferation of blackened fish on San Francisco menus, most being riffs on the Creole blackened catfish and redfish recipes. Jan Birnbaum, a chef who worked with Prudhomme during the peak of the Bay Area’s love affair with Cajun food, was the most famous local chef cooking Louisiana-inspired food at his restaurant, Catahoula in Calistoga.

As years turned into decades, San Francisco’s African American population dropped by more than half. Some of those families have found their way to the East Bay, with Oakland, Richmond and Antioch seeing a steady number of new Louisiana restaurants.

“When there’s a lack of representation in a food category, there has to be more of an explanation done when it comes to the food,” said Jay Foster of Farmer Brown. “People are unfamiliar and that makes it a bit harder to get them in the door.”

In the city, health-oriented, fast-casual restaurants are growing quickly with chains like Asian Box, with its gluten-free menu, and Mendocino Farms, which sells a “fried” chicken sandwich that isn’t actually fried but instead is roasted and topped with bread crumbs. Little Gem, a Hayes Valley business with a menu that comprises gluten- and dairy-free items, opened a second location earlier this year in Cow Hollow.

That’s all in contrast to the heavier fare native to Louisiana.

“It’s just kind of hard to get people in for gumbo or jambalaya in the afternoon or an early dinner,” Chun said.

This isn’t to say Louisiana food can’t be found in the city. Queen’s Louisiana Poboy Cafe in Portola has relocated to the Embarcadero. Auntie April’s in the Bayview touts soul food, but its menu has a number of Louisiana dishes.

The lone success story, it seems, is Brenda’s French Soul Food, on Polk Street since 2007. The restaurant still draws crowds for brunch and dinner, especially on the weekends. Chef-owner Brenda Buenviaje has opened a sister restaurant on Divisadero, and is plotting another outpost in Oakland later this year.

“At this point, it kind of feels like Brenda’s is really the only game in town,” said Chun.

The main reason for its outlier success may be because its food is, simply, great, said David Nayfeld of Divisadero’s buzzy Italian restaurant Che Fico.

“They don’t try to make anything really fancy or pretentious,” Nayfeld said. “It’s just soul food done well. If it’s a fried shrimp poboy, the shrimp is simply fried exceptionally well.”

But this isn’t the only reason Brenda’s is successful where other businesses fail. The Cajun and Creole aesthetic associated with Louisiana food often devolves into a campy caricature of itself when re-created outside of its home state.

“The allure of this food is the location; it’s location specific,” Pier 23 Restaurant’s Altman said. “Out of the context of being in New Orleans, restaurants that open as a Cajun or Creole place, it’s hard for them not to be kitsch.”

Brenda’s, meanwhile, takes a minimalist approach in design. Mirrors, common in many older restaurants and residences in Louisiana, hang on the walls to evoke the spirit of the state, but that’s about it. There are no alligators hanging from the walls, large street signs for Bourbon Street or shelves overflowing with colorful Mardi Gras beads. Brenda’s is honest in its realism, preferring to scale back in order to convey authenticity.

Here, it’s the beignets, some stuffed with crawfish, some filled with apple and sweetened with cinnamon honey butter, that bring diners back. The catfish is flaky and well-seasoned. Shrimp and grits come with tender shrimp, tomato and green onions, all steeped in Creole spices.

“People just want good food. You can’t please everyone, that’s just the way it is, but I still like doing this and people seem to enjoy it,” Buenviaje said.

Brenda’s may be the template for New Orleans-inspired success in San Francisco: simplicity and honesty rule.

“I think people will always love the food,” Buenviaje said. “I don’t think it’s going anywhere.”

A previous version of this story misstated Joey Altman’s job title. He is currently director of culinary operations at Pier 23 Cafe Restaurant & Bar. The story has been altered to reflect this change.

Justin Phillips is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email:jphillips@sfchronicle.com. Twitter:@JustMrPhillips