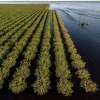

Construction crews work on the Central Valley segment of the high-speed rail line in Fresno, Calif. on Sept. 23, 2021.

Peter DaSilva/Special to The ChroniclePlans for a bullet train line that could zoom passengers from the Central Valley into downtown San Francisco took a major leap forward this week when rail officials signed off on the 43-mile extension.

加州的嗨gh-Speed Rail Authority Board voted unanimously Thursday to sign off on a preferred route and environmental clearance for the segment that would carry fast trains from San Jose into the city by sharing electrified track with Caltrain’s commuter trains.

The line could open for service by as soon as 2033, the authority projects. Stations are slated for San Francisco International Airport/Millbrae and the Caltrain Mission Bay station at Fourth and King streets, which would eventually be replaced by a station in the basement of Salesforce Transit Center.

Major hurdles to the project remain. For starters, California hasn’t figured out where it will get up to $25 billion needed to build the San Francisco and Silicon Valley bullet train extensions.

Nevertheless, approval of the project’s final spur north into the heart of the Bay Area is a significant milestone. It’s also the latest in a series of wins for high-speed rail in recent months, a reprieve after years of spiraling costs and litigation caused some Democratic state legislators to consider pulling the plug.

今春早些时候,铁路管理局董事会从新加坡oved the train’s90-mile segment to connect Silicon Valleywith Merced in the Central Valley; construction has been under way in the Central Valley for about seven years.

Then, state legislators agreed in June to release $4.2 billion in bonds to complete construction on the project’s Central Valley line, ending a years-long standoff that was largely fueled by anger over California’s decision to build the train outward from the Central Valley first, rather than inward from Los Angeles and the Bay Area.

Brian Kelly, CEO of the Rail Authority, said all those developments put together show the authority is doing what it’s promised to do for years: build the most financially feasible segment of the train first while continuing to make headway on extensions to the state’s most populous coastal regions.

“There’s a realization, a reality, that construction started where it started,” he told The Chronicle. “The fact of the matter is that the federal government gave us money to start in the Central Valley.”

最初,铁路局计划构建track inward from Los Angeles and the Bay Area, including lines running east from San Francisco and Silicon Valley. Gov. Gavin Newsomstunned many state legislatorsand rail advocates in 2019 when he announced he would focus first on the Central Valley line due largely to rising costs.

The Rail Authority’s push to approve plans and environmental clearance for extensions to the Bay Area and Los Angeles is, in part, designed to assure voters the project remains statewide in its scope.

Democrats in the state Assembly, led by the powerful Los Angeles delegation, had pushed for years to take a chunk of the $4.2 billion in bond funds for the Central Valley line and instead spend it on regional transportation projects in major metro areas that could eventually connect with high-speed rail.

But that standoff ended in June, when the Rail Authority emerged with its bond funding intact, though its operations will be overseen by a new inspector general. Lawmakers also dropped a push to cut costs by using diesel-powered trains, rather than electrified track, in the Central Valley.

Kelly, who has led the authority for 4½ years, said that for the first time in a long time it feels like the bullet train is making significant progress, rather than merely fighting for its political and financial survival.

“We’ve gone from a conversation of ‘What are we going to do?’ to ‘Let’s go do it,’” he said. “We’ve turned a corner a little bit with that budget deal.”

California votersapproved $9.95 billionin bond funding for high-speed rail in 2008, with the promise that money would be used to help build a 220-mph train to deliver riders between the state’s biggest regions in under three hours.

But the project has faced ridicule overrepeated construction delaysand soaring costs, with its total budget growing from $33 billion to at least $105 billion in the Rail Authority’s latest business plan — and potentially many billions more when the authority factors recent inflation into its estimates.

Trains were initially supposed to start running in 2020. Now, the agency doesn’t anticipate the first trains will start running in the Central Valley until 2029, followed by Silicon Valley in 2031.

Construction crews work on the Central Valley segment of the high-speed rail line in Fresno, Calif. on Sept. 23, 2021.

Peter DaSilva/Special to The ChronicleAssembly Member Laura Friedman, a Democrat from the Los Angles area who chairs the Transportation Committee, is among the legislators who remain skeptical about the direction of the train’s Central Valley segment. She said she was elated to see an inspector general created to “ensure accountability and transparency.”

Friedman said she worries the Rail Authority doesn’t have a viable plan to bring enough riders onto the Central Valley segment when it’s completed because there isn’t a clear, immediate way to connect with riders in the Bay Area.

“For it to be successful, it’s my contention that it needs to link into places that people want to go,” she said. “I hope that the money they have left is enough to get them something that is a workable system with a connection into the Bay Area.”

Bond funding that the Legislature approved this summer reflects the remainder of the project’s voter-approved funding and is expected to be exhausted by the time construction is done on the first 171-mile stretch from Merced to Bakersfield.

That means the Rail Authority likely would be asking the federal government and California voters to approve funding for the project’s next construction phases, with its Silicon Valley and San Francisco segments.

In that sense, the Rail Authority Board’s approval of the San Francisco segment this week was an important jolt of momentum for rail supporters, who are still working to repair the project’s public image in the wake of discontent over the Central Valley-first approach.

“The more that we can make it real for people, that always helps in that conversation,” said Boris Lipkin, the authority’s Northern California regional director. “Some of the best things we can do are to show that progress.”

Planning approval in the Bay Area is also a symbolic win for rail supporters, who have long said the project would help level inequities between the Central Valley and the state’s wealthy coastal areas. Supporters of the project pitched high-speed rail as a way to link the state’s low-income interior and its affordable housing with high-paying jobs on the prosperous coast.

The project’s San Francisco segment would share track with Caltrain’s slower commuter trains, so trains could run from San Jose’s Diridon Station up the Peninsula into the city without laying new track.

铁路官员早些时候考虑建立separate high-speed rail corridor on the Peninsula, but that effort was abandoned years ago due to opposition from homeowners in the affluent region.

Caltrain is now working to electrify its system and has received about $700 million from the Rail Authority for the effort. Its commuter trains run at 79 mph, but the system could share track with faster trains, which would operate at 110 mph in the region, thanks to a series of existing passing lanes.

In other parts of the state, the bullet train is slated to operate faster, approaching speeds of up to 220 mph in the Central Valley.

San Francisco’s segment would be part of the bullet train’s 500-mile Phase 1, which ultimately aims to zip riders from San Francisco to Anaheim. With approval of the San Francisco extension, 420 miles of that first phase have been environmentally cleared, which allows rail officials to begin advanced design work.

Rail Authority officials are hopeful the project can sustain its recent streak of momentum as it applies for $8 billion in additional federal grants. The Biden administration has set aside tens of billions of dollars for new rail projects.

Still, the project faces critics who say it’s drifted too far from the statewide system voters approved in 2008. Quentin Kopp, a retired state senator and former chairman of the Rail Authority Board, laughed at the idea of bullet trains running into downtown San Francisco.

“That’s called much ado about nothing,” he said. “This is destined for the graveyard of boondoggles now.”

Dustin Gardiner (he/him) is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email:dustin.gardiner@sfchronicle.comTwitter:@dustingardiner