“Hideous nonsense.”

“Authentic architectural butchery.”

“An affront to San Francisco.”

The reviews of the Transamerica Pyramid, coming from around the world after the 1969 design reveal, were uniformly savage. The Chronicle’s architecture critic testified against the building at City Hall. Dozens of Telegraph Hill residents protested the construction zone in dunce caps. San Francisco’s own city planner called the tower “an inhumane creation.”

And yet the Transamerica Pyramid, built on a foundation of white-hot controversy, still rose high at the end of Columbus Avenue — and emerged as an iconic symbol of San Francisco. In a city where despised projects become beloved (hello Sutro Tower!), pyramid is king.

July 28, 1971: Transamerica Pyramid under construction in downtown San Francisco, as seen from Columbus Avenue.

Clem Albers/The ChronicleWith the building celebrating its 50th anniversary later this year, we looked through The Chronicle for the best photos of the skyscraper’s construction — and the harshest reviews.

The announcement of the building in The Chronicle was uncontroversial enough, written with the enthusiasm of a story announcing Santa Claus’ arrival at a local department store.

“A pyramid, so unusual it might have drawn a wink or a gasp from the Sphinx, was unveiled yesterday as the next addition to San Francisco’s skyline,” Chronicle reporter George Draper’s story began. “It will cut into the sky like a stiletto, rising 1,000 feet above Montgomery Street between Clay and Washington, and it will serve as the global headquarters for Transamerica Corp.”

A first look at the Transamerica Pyramid appeared in the Jan. 28, 1969, edition of the San Francisco Chronicle.

Chronicle archiveThe 1969 design was just over 1,000 feet, making it the tallest point in San Francisco, peering over Mount Davidson at 925 feet. (Sutro Tower, anurban design controversyfor another day, was completed years later in 1973.)

Nicknamed the “splendid splinter” by critics, it was met with immediate derision by the city’s planning director, Allan Jacobs, and redesigned into a shorter and stubbier model — at 865 feet still the tallest building in the city.

Futuristic architect William Pereira, who came from Los Angeles and had worked as a Hollywood art director, insisted his new skyscraper would be good for the city.

“This pyramid design allows more light and more air into the streets and conserves the view,” he told The Chronicle. “All in all, I think we have a valid, rational design and, if you’ll forgive me, a handsome one.”

If anything, Pereira’s redesign was more unpopular. Architecture critics from San Francisco and far beyond rallied against the construction. A few highlights from the pile-on:

Progressive Architecture magazine:“Insensitive, inappropriate, incongruous, inescapable and in the wrong place.” and “No less reprehensible than … destroying the Grand Canyon.”

Chronicle architecture critic Allan Temko:“Authentic architectural butchery. … This building would even be wrong in Los Angeles, where it was hatched, or in Las Vegas, where it belongs, or in Dallas, where buildings vie for attention. It certainly doesn’t belong in San Francisco, which is sensitive and easily hurt.”

Los Angeles Times critic John Pastier:“企业,更重要的是city have exercised considerably more restraint in their architecture than Transamerica, which is blatantly attempting to put its ‘brand’ on the city. This is antisocial architecture at its worst.”

July 23, 1969:

Washington Post critic Wolf Von Eckardt:“Tastes change. But not the taste of tastelessness.” The pyramid is “hideous nonsense” and “a second-class world’s fair space needle.”

The critique that ages the most poorly came from Assemblyman John Burton, who said the pyramid would “rape the skyline of San Francisco and virtually destroy the delicate beauty of Telegraph Hill and the Jackson Square area of the city.”

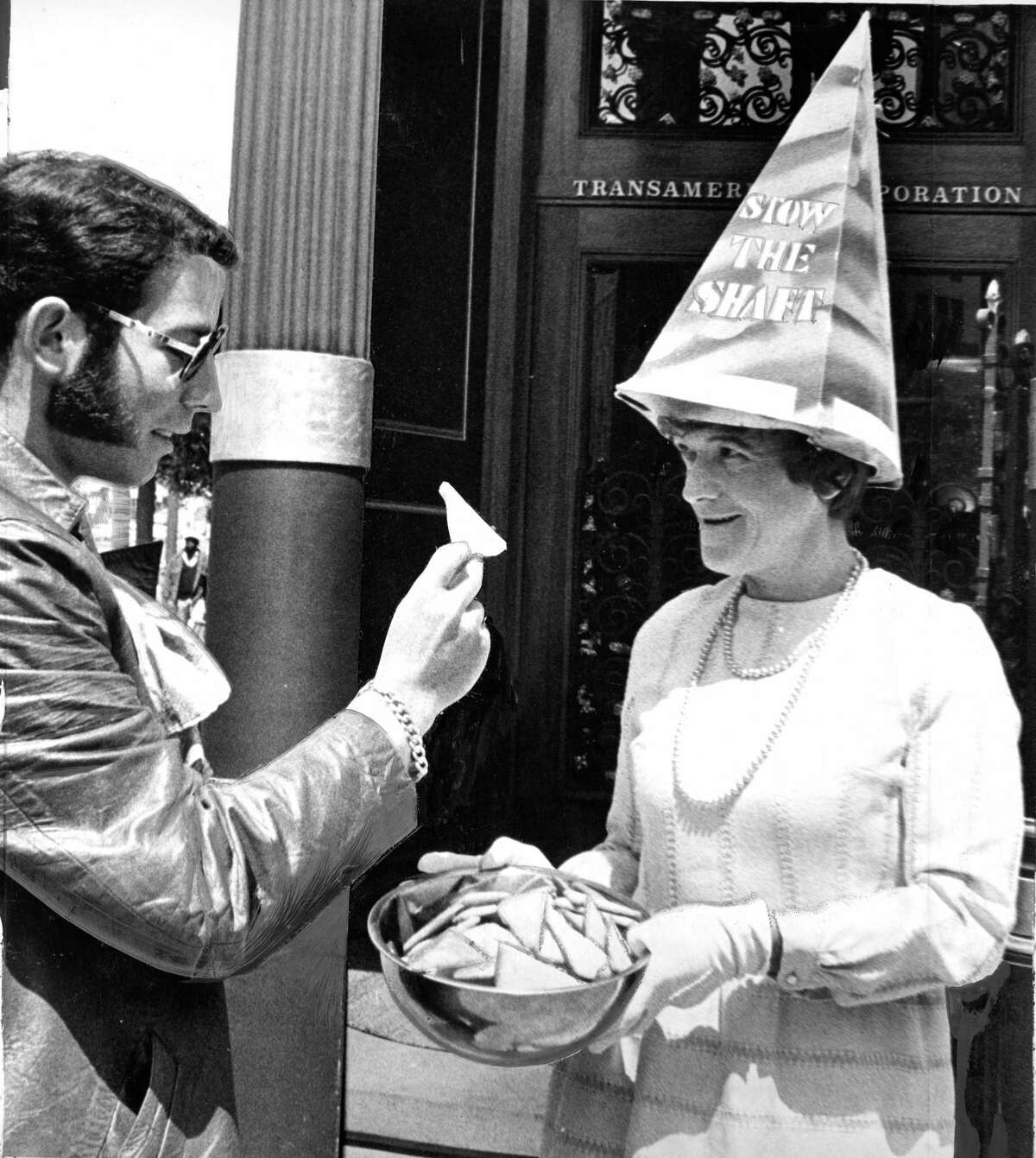

Transamerica officials seemed to be all smiles through the onslaught, to the point of passive aggression. On one afternoon in 1970, pyramid officials passed out fortune cookies to protesters with jokey pro-pyramid messages inside.

July 23, 1969: Sally Walker passes out pyramid-shaped cookies during the demonstration against the building of the Transamerica Pyramid.

Stan Creighton/The ChronicleHerb Caen reported that Transamerica Vice President John Chase showed up to a protest in North Beach, where opponents wore “Stop the Shaft” dunce caps and a Transamerica Pyramid-shaped cake was served. Caen wrote: “Attorney Francis Carroll lopped off the top and presented it to Chase, with the plea, ‘Please take a piece of cake instead of a chunk of San Francisco.’”

Meanwhile, San Francisco Mayor Joe Alioto tripled down on his defense of the building. There is no reason, he said, that San Francisco should have “a monopoly on rectangular slabs.”

Ultimately, Alioto had the Planning Commission on his side, along with the Chamber of Commerce. (The San Francisco Chronicle editorial page was also pro-pyramid, ignoring the protests of Caen and Temko.) Despite a lawsuit from Telegraph Hill residents, a push from Supervisor Jack Morrison to move the pyramid to SoMa and many letters to the editor, the pyramid went up quickly. It cost $32 million and was finished in summer 1972.

This is a carousel. Use Next and Previous buttons to navigate

Chronicle photographers seemed to love the pyramid’s aesthetics, and covered its rise with artistic detail.

Joe RosenthalandClem Albers, historic World War II photographers, captured stunning images of the half-built icon. Photos were taken from a helicopter. Once the skyscraper was near-complete, photographers took skyline photos from five different neighborhoods in the city. (Many of the images with this column have never been published.)

And then something surprising happened. The pyramid became a classic. It’s on postcards and in snow globes. Subsequent skyscrapers are compared (often unfavorably) to it. In the “Star Trek” movie and TV universe, where Starfleet is headquartered in San Francisco in the 24th century, the only surviving structures are the Ferry Buildingand the Transamerica Pyramid.

Thirteen years ago, Chronicle urban design critic John Kingcaught up with pyramid critics. Henrik Bull, an architect who denounced the proposal at hearings and rallies, told King: “What’s good about the pyramid overwhelmed what’s bad about it. It’s a wonderful building. And what makes it wonderful is everything we were objecting to.”

Alioto lived until 1998, long enough to see several anniversaries, and his predictions come true. For one issue, at least, he was the city’s Emperor Norton, clearly seeing into the future, even as the loudest voices declared him to be completely crazy.

1972年6月19日:泛美金字塔接近尾声f its construction as seen from Columbus Avenue.

Art Frisch/The Chronicle“I looked once more last week at the Chrysler Building in New York and believe it to be the best building in that skyline,” Alioto said in 1969. “My personal opinion remains that future generations of San Franciscans may well make a similar judgment on the Transamerica building.”

Peter Hartlaub (he/him) is The San Francisco Chronicle culture critic. Email:phartlaub@sfchronicle.comTwitter:@PeterHartlaub