This is a carousel. Use Next and Previous buttons to navigate

The Blue Angels rocketed over San Francisco in 1950, and this time nobody was complaining about the noise.

The precision flying team arrived in the city piloting F9F Grumman Panthers painted black for combat, no doubt more nervous than any Blue Angels team in history. Their next stop after San Francisco would be Korea.

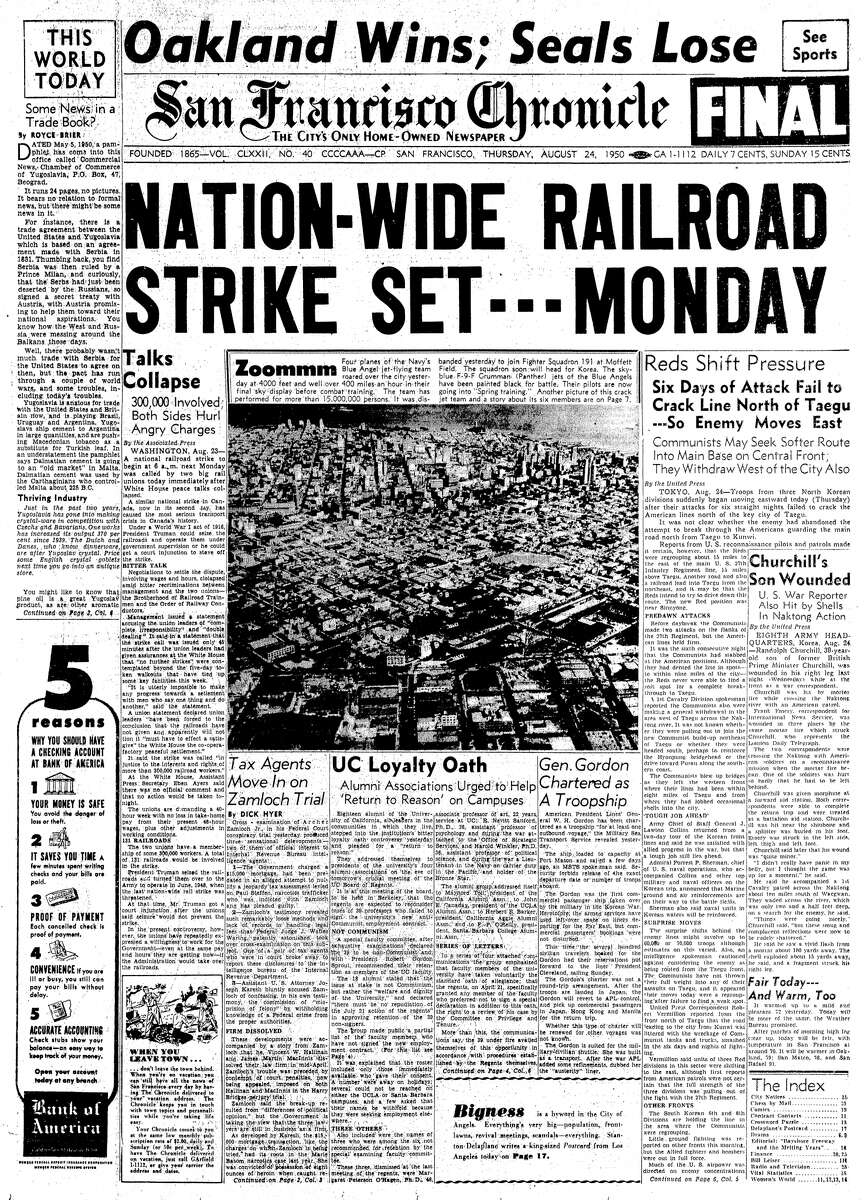

Pierre Salinger, then a San Francisco Chronicle reporter and years later press secretary for John F. Kennedy, broke the news.

“The famed Blue Angels, a flying team, which toured the Nation to show the citizens the utmost in precision flying, was disbanded yesterday in a quiet ceremony at the Naval Air Station, Moffett Field,” Salinger wrote in the Aug. 24, 1950, article. “They became members of the fighting squadron 191, which is completing training before heading west — west to war.”

The special time in Angels history was documented with some unforgettable photos. As a send-off to the team, the U.S. Navy took four images from above their altitude of 4,000 feet, looking down at San Francisco. Golden Gate Park, Seals Stadium and other landmarks can be seen far below. They remain some of the most striking military photos in the Chronicle archive, right up there with the1951 photos of San Francisco, taken from the submarine Catfish’s periscope.

The Blue Angels were formed in 1946, and their earliest Bay Area performances had been in the East Bay. The team’s 1949 exhibition at the Oakland airport included two local pilots; Jack Robcke of San Francisco and Edward F. Roth of Palo Alto. (It was a different world, still 60 years before social-media-related privacy concerns. As was The Chronicle’s style at the time, the pilot addresses were printed in the paper, along with the names of their parents.)

But the 1950 show was special. The team made the front page for the first time and the local pilots were interviewed for the paper, expressing confidence in their combat mission ahead. Robcke, a 1940 Mission High School graduate, said as experienced as the pilots were flying from a military airport, most of the Angels needed to learn how to take off and land from an aircraft carrier.

“We’re just a bunch of pilots who know how to fly,” Robcke said. “We have to become a team. Just the same as in football.”

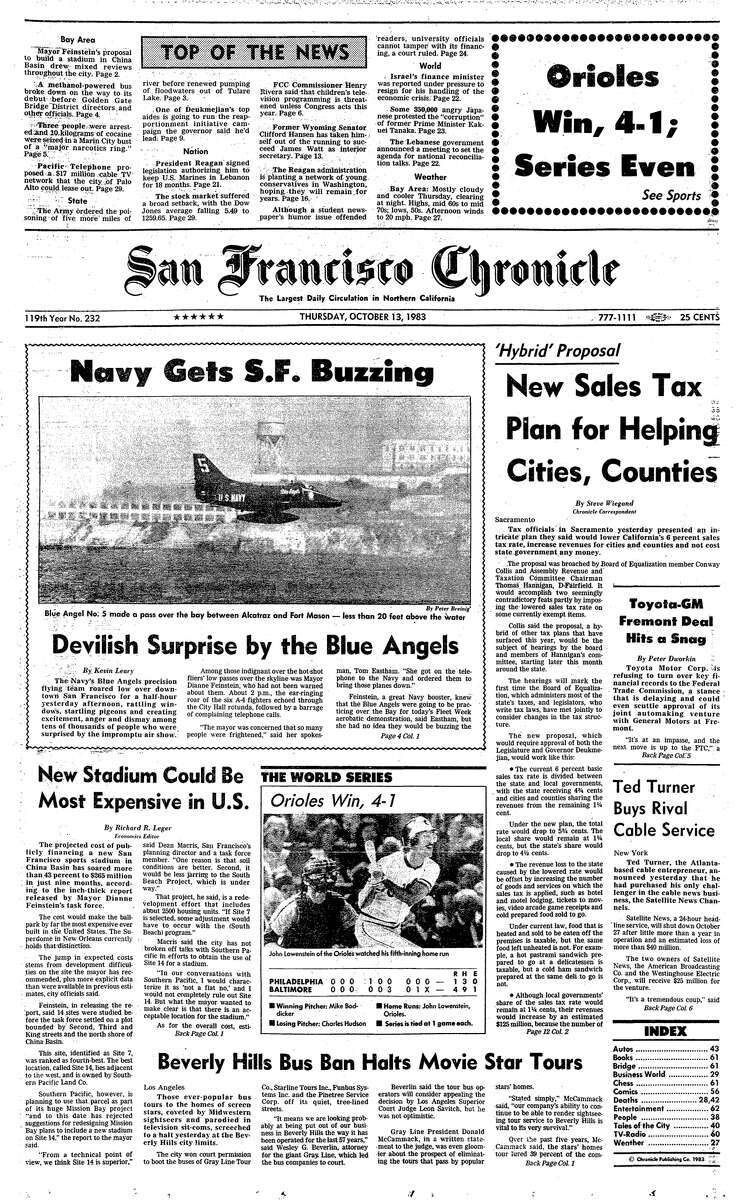

Fleet Week wouldn’t return to San Francisco for 30 years, when the modern Columbus Day week tradition started in 1981. That celebration featured the Blue Angels in A-4 attack jets, over a city that in three decades had shifted from ruled by Republicans to an epicenter of liberal values.

That honeymoon lasted two years, before Fleet Week became the polarizing entity it is today. “Devilish Surprise By Blue Angels,” a Chronicle headline read on Oct. 13, 1983, before documenting complaints (and a few raves) from citizens who thought they flew too low over downtown San Francisco.

“I thought the Russians were coming when I heard the jets,” said downtown worker Diane Comer. “I thought Reagan had done something and we were going to get it.”

The Chronicle’s Kevin Leary wrote the front-page story:

“Among those indignant over the hot-shot fliers’ low passes over the skyline was Mayor Dianne Feinstein, who had not been warned about them,” Leary wrote. “About 2 p.m., the ear-ringing roar of the six A-4 fighters echoed through the City Hall rotunda, followed by a barrage of complaining telephone calls.”

Feinstein would come around. She had been an outspoken supporter of Fleet Week. But the public would remain split on the issue, sending annual letters to The Chronicle hailing the tradition, criticizing the militaristic display, or writing on behalf of their frightened dogs.

It wasn’t that way in 1950, when the entire population looked to the sky and was in close to full agreement that they were looking at heroes executing an awe-inspiring display of military might.

Among those who continued to support Fleet Week in the modern era was pilot Robcke. He made it back from Korea safely after flying off the Hornet, settled in the Bay Area, and was a Fleet Week regular in his retirement years, according to his Chronicle obituary. Robcke died in 2010 at his home in Walnut Creek, surrounded by family.

Peter Hartlaub is The San Francisco Chronicle’s pop culture critic. Email:phartlaub@sfchronicle.comTwitter:@PeterHartlaub