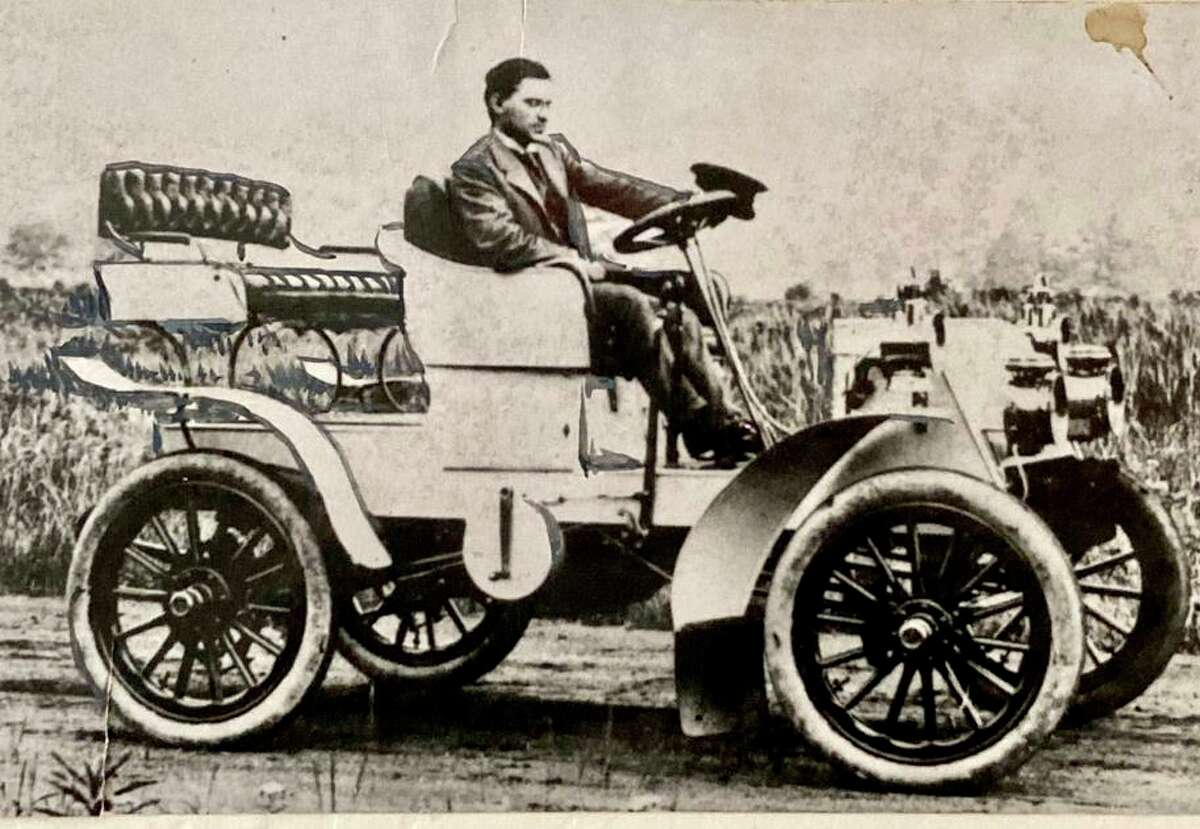

A motorist rides through a park in the early 1900s in a photo from the archives. A battle over cars in Golden Gate Park raged 115 years ago, with xxx

File photo“Special policemen should be stationed in the Park, armed with shotguns, to shoot the tires of automobiles exceeding the speed limit.”

Those were the heated words of William H. Metson, president of the Golden Gate Park Commission, at the peak of an early 20th century battle over cars inGolden Gate Park.

The clash among lobbyists, park leaders, car-lovers and the citizens who were injured by automobiles has mostly been lost in time — overshadowed in nostalgic media by a San Franciscomayor who was imprisoned in 1907, graft trials anda certain earthquake and firethat wiped out most of the eastern half of the city.

But there are some important parallels between that 1902 to 1911 debate andthe current battleto remove cars from a 1½-mile stretch of John F. Kennedy Drive, which appears to be coming to a final decision with a Board of Supervisors vote this winter. If nothing else, it proves that San Franciscans have always been polarized when it comes to using our greenest spaces as freeways.

The first personal automobiles began arriving in San Francisco in the earliest years of the 20th century. And the first arrest of a motorist, according to Chronicle records, occurred near the park on Sept. 10, 1902 — when mounted policeman M.J. Greggain pulled a driver over for speeding on what is now the Great Highway.

“Ignorance of the law worked well yesterday for P. Hewlett,” The Chronicle reported. “He was so busily employed in keeping his automobile clear of other vehicles that for a time he did not hear the warnings of the officer.”

At the time there were fewer than 500 cars registered in Northern California. But Golden Gate Park Superintendent John McLaren, the architect of the park, was a naturalist who was wary of museums anddeplored the idea of statues, let alone vehicles. While cars were free to travel the rest of the city’s roads, San Francisco reportedly became the only major city to ban cars from its parks outright — a restriction that lasted for three years.

Enter the lobbyists from the Automobile Club of America (yes, there were pro-car lobbyists in the early 1900s), who on May 6, 1905, brokered a probationary deal: Cars would be permitted in the park during daylight hours but limited to a speed of 8 mph, and only licensed autos displaying badges were allowed. Motorists promptly broke all of the rules, reportedly using the park day and night as a joyriding shortcut to places such as the Cliff House, then a seven-story Victorian chateau.

Horse riders in the park raged, with stable owners asserting to the Park Commission that “the machines were driven at a high rate of speed, regardless of regulations, and constituted a menace to man and beast, and are driving horses entirely from the park,” according to a May 20, 1905, Chronicle article.

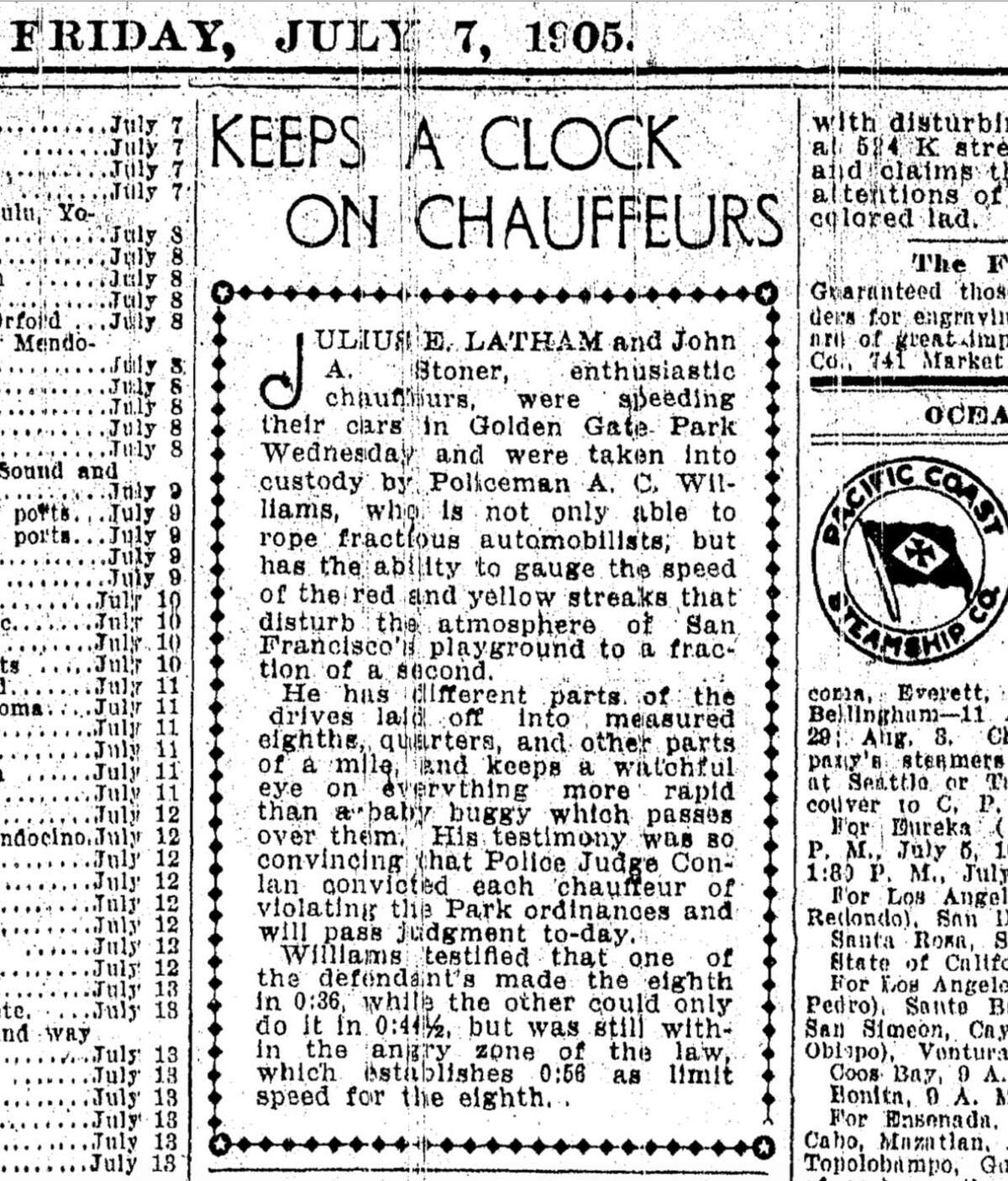

A 1905 Chronicle article detailed a police officer creating a speed trap in Golden Gate Park.

The Chronicle 1905这导致了英雄像警官J.C.威廉ms, who may have devised the region’s first speed trap. The newspaper reported Williams “has the ability to gauge the speed of the red and yellow streaks that disturb the atmosphere of San Francisco’s playground to a fraction of a second,” by measuring off an eighth of a mile on the main roads with markers, and timing drivers at then-blistering speeds of around 15 miles per hour.

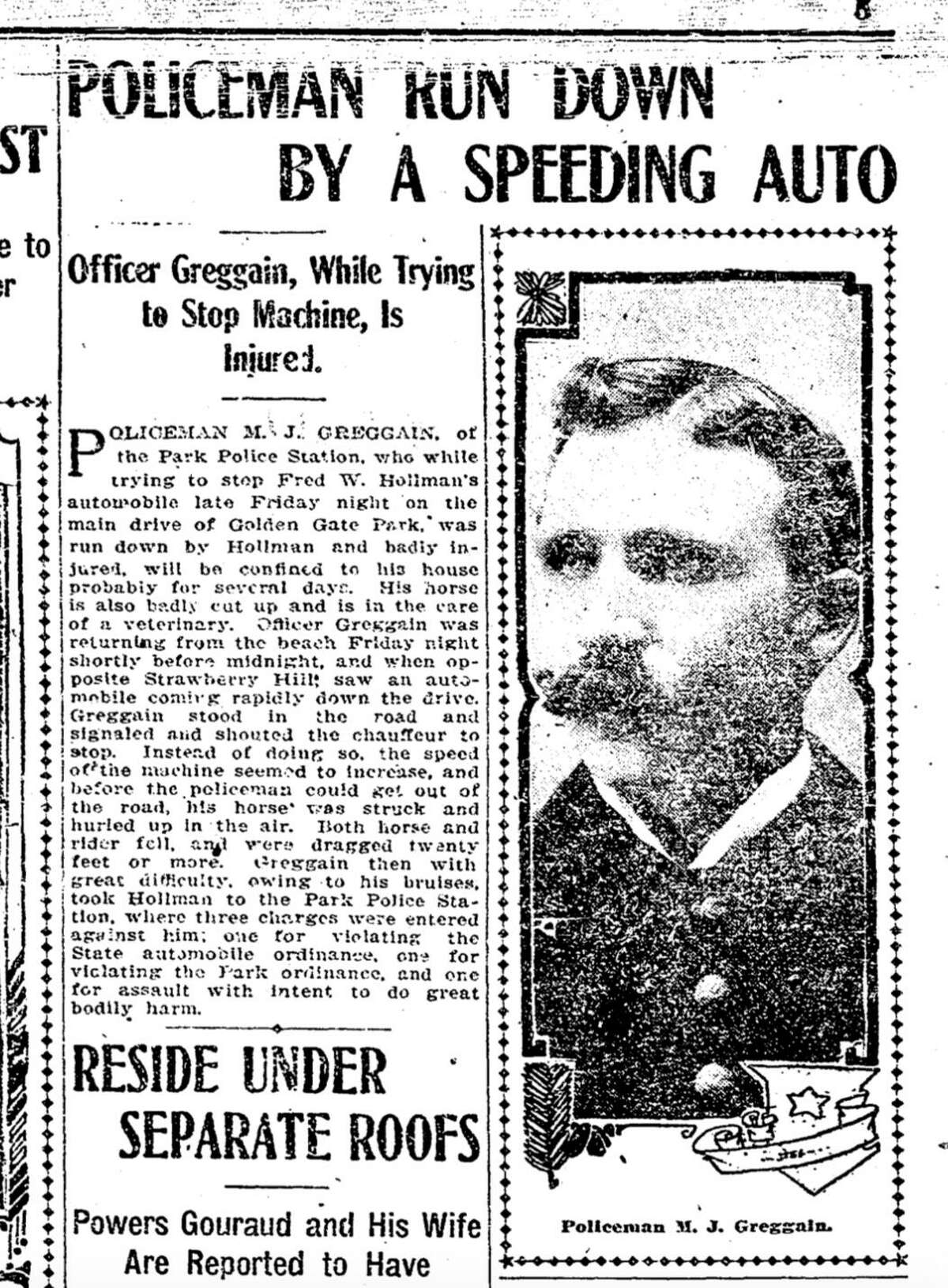

The 1906 earthquake and fire quieted the controversy briefly, with refugeesmoving into San Francisco parksby the tens of thousands. But in October 1906, police Officer Greggain — the same officer who arrested that first motorist — was seriously injured at midnight by a speeding driver on the main drag of Golden Gate Park.

“Greggain stood in the road and signaled and shouted at the chauffeur to stop,” The Chronicle reported. “Instead of doing so, the speed of the machine seemed to increase, and before the policeman could get out of the road, his horse was struck and hurled up in the air. Both horse and rider fell and were dragged 20 feet or more.”

伤痕累累的Greggain仍然拖司机量子d W. Hollman to the Park Police Station and charged him with assault with intent to do great bodily harm.

The Chronicle in 1907 covered a Golden Gate Park policeman who was hit by a car. His horse was also injured.

Chronicle archives与此同时,汽车变得越来越快the injuries they caused more severe. (By 1911, drivers arrested for speeding were topping 30 mph.) Park officials reported that heavier cars were damaging roadways meant for pedestrians.

In just two years, the Automobile Club of America had pivoted from happy talk and broken promises to more of a scorched earth attack — joined by lobbyists from the Automobile Dealers’ Association plus a team of lawyers. They argued in 1907 that because cars now outnumbered horses in the park, drivers had established dominance and should have no restrictions.

“There are enough owners of automobiles in San Francisco and vicinity, and there is enough money invested in its automobile business, so that they need not in my opinion submit to unfair discrimination,” pro-car advocate C.A. Hawkins said at a June 13, 1907, meeting of the Park Commission. “If that fails, (we will) organize and go into politics strong enough to see that the next Board of Park Commissioners are men who are more fair-minded than the present Board.”

Despite that overt threat, the park leaders continued to resist. Finally, on July 4, 1907, Park Commissioner Metson let loose with his shotgun-to-the-tires suggestion. In a Chronicle article headlined “Buckshot for Speeding Autos,” McLaren himself spoke of his own recent incident of “rank indifference” from a motorist in violation of park rules who “refused to recognize the superintendent’s authority and rudely thrust him aside.”

Above: Marshal Dill (left) and John McLaren shovel manure in Golden Gate Park in February 1940.

File photo 1940米特森医生后来奖励公园生涯with Metson Lake, which remains one of the underrated gems of Golden Gate Park. McLaren’s name is on a San Francisco lodge, an avenue, a reservoir and the city’s second biggest park.

Minus the threats of gunfire, the parallels between the 1907 and 2021 car battles in the park are uncanny. Both involve lobbyists for pro-car forces, claims of discrimination, drivers using park roads as a commute shortcut and a recent history of car-related dangers in pedestrian spaces that are decried but not addressed.The modern fight for JFK Driveto preserve pandemic adaptations and be restored to walkers, bicyclists and skaters is being cast as 50 years in the making. But really it’s a century-overdue partial return to the park’s original state: embracing nature, and resisting machines.

That unrealized buckshot threat turned out to be the peak of strained relations between car interests and park leaders. It was mostly a cold war until 1911, when McLaren showed up in the paper, sitting in Chalmers-Detroit 30 touring car, gifted from the city to McLaren and the park. It retailed at $2,500 — about $70,000 in 2021 dollars — plus whatever it cost to stencil the words “Golden Gate Park” in gold letters on each door panel.

Automobiles line up at the Ferry Building in San Francisco in 1915, waiting for a ferry arrival from Sausalito.

Chronicle file photo 1915The Chronicle hailed the event like a moon landing.

By then, San Francisco and its press were in love with cars, and automobile dealers had already started a grand auto row on the spine of the city along Van Ness Avenue. In the years that followed, there would be car rallies past major monuments, car-related tourism and, eventually, automobile races in Golden Gate Park.

“Golden Gate Park and the automobile have at last joined forces,” The Chronicle reported on June 27, 1911. “To the users of automobiles in San Francisco this is probably as important a single event as has occurred since motor cars were put into use. … Soon there will be no roads open to horses that automobiles will not use too.”

Peter Hartlaub is The San Francisco Chronicle’s culture critic. Email:phartlaub@sfchronicle.comTwitter:@PeterHartlaub