When San Franciscans were first asked to don masks as theSpanish flu of 1918raged through the city, the idea was met with patriotic fervor.

Even before the mandatory order was approved by supervisors on Oct. 24, 1918, The Chronicle reported, 4 out of 5 citizens were already wearing face coverings on the streets.

“A week ago I laughed at the idea of the mask,“ local Red Cross Chairman John A. Britton told a reporter. “I wanted to be independent. I did not realize that the cost of such independence was the lives of others.”

That sentiment would change to outright defiance in the months that followed.

Today, San Francisco is a progressive model of compliance during the 2020 coronavirus pandemic. But a century earlier it more closely resembled the hotbeds of conflict that we’ve seen today in Michigan and Oklahoma. “Mask slackers” were hauled into court by the hundreds, a health official shot an unmasked protester, and an Anti-Mask League formed — with meetings that drew thousands.

Mayor James Rolph, the Board of Supervisors and health officials were in lockstep when they ordered mandatory masks in public. At that point, there were 385 deaths in San Francisco related to the influenza, a number that would increase tenfold.

The first few days were filled with bright stories about mask fashion and do-good volunteer groups sewing for the cause. But by the end of the first week, there were signs of defiance.

The Chronicle reported on Nov. 2, 1918, that 175 were arrested, including some “who were wearing their masks draped over their chins while they enjoyed their morning pipe.” While most pleaded ignorance and paid a $5 fine, a vocal mask opposition was also emerging.

“John Raggi, arrested on Columbus Avenue, said he did not wear a mask because he did not believe in masks or ordinances, or even jail,” The Chronicle reported. “He now has no occasion to disbelieve in jails. He is in the city prison.”

Mask-related defiance became violent. A Chronicle story headlined “Three Shot in Struggle with Mask Slacker,” gave a detailed account of health department inspector Henry D. Miller confronting mask-less blacksmith James Wiser, who was on a street corner telling a crowd “they are the bunk!”

“At the door of the store the blacksmith struck Miller with a sack containing a large number of silver dollars, and then knocked him to the ground,” The Chronicle reported. “While being pummeled, Miller drew his revolver, and four shots rang out.”

No one died, but two bystanders were hit. Both men were arrested.

Later in the year, a small bomb was found addressed to Dr. William C. Hassler, a sort ofDr. Anthony Fauci-type figure during the pandemic. It was filled with glass and buckshot and came with a note that said “compliments of John.”

Nicole Meldahl, executive director of the San Francisco history groupWestern Neighborhoods Project,said “there was already turmoil happening in the city” and state, pointing to the 1916 and 1917 bombings of the Preparedness Day Parade in San Francisco and the governor’s mansion in Sacramento. Tensions peaked after labor leader Thomas Mooney was convicted of the first bombing, in what looked like a rigged trial.

“Just as we’re seeing now, a crisis — whether that be war or whether that be a pandemic — it just kind of exposes the cracks in the system,” Meldahl said.

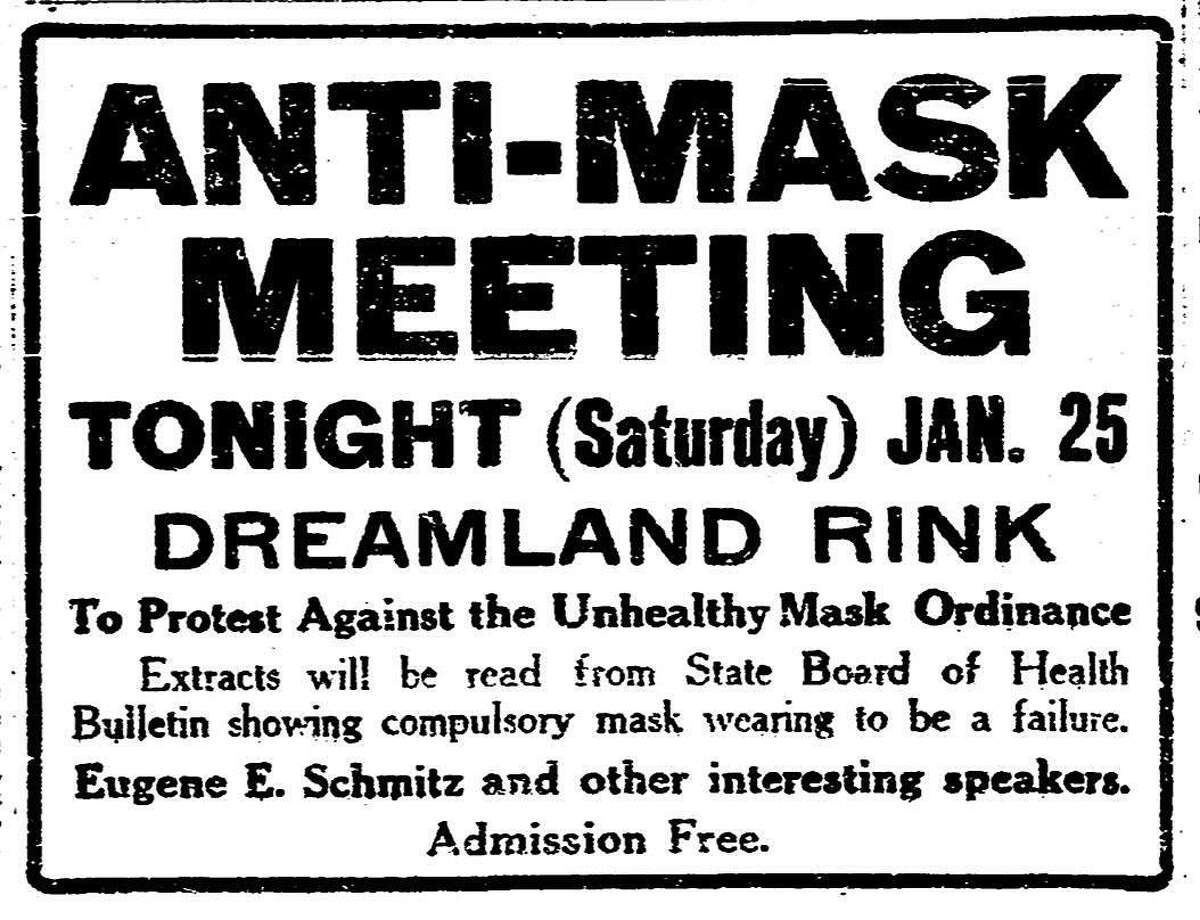

Victory was declared over the virus in late November. When the influenzareturned in January,protests became more organized by the new Anti-Mask League, which advertised in newspapers and rented spaces that could seat thousands.

There was a Tea Party-like fervor to the league, and their central argument. When the virus returned, city leaders had capitulated to business leaders, refusing to close churches and theaters as they did in the fall — effectively protecting corporate interests, while forcing common citizens to don masks.

At the same time, the league offered mostly personal attacks, not practical alternatives. And topping its list of allies was disgraced former San Francisco Mayor Eugene E. Schmitz, who had been convicted of extortion and jailed after the 1906 earthquake and fire.

The Chronicle reported that the first meeting drew 2,000 spectators. Meldahl said the league chairwoman was Emma Harrington, an attorney, activist and the first woman to vote in San Francisco in 1911.

“People had just had it,” Meldahl said. “They had spent years under war rationing, sending their sons off to war, sending their daughters off to war. And then you fold all this in with an ambitious woman who was trying to move her way up, and kind of a scheme-y local politician who found a way to stick it to Rolph.”

不像当今在斯蒂尔沃特市的领导,Okla., where a mayor reversed the city’s mandatory mask plan as a response to threats, San Francisco of 1919 made no concessions.

After the first meeting, public comments from Hassler and other officials seemed directed at the league.

“We cannot in this matter pay any attention to any public agitators against the mask for the obvious reason that the question is one of public health and not of like or dislike of the mask,” said Arthur H. Barendt, president of the San Francisco Board of Health.

On Jan. 15, 1919, the day before masks were reinstated, public health officials reported 510 new influenza cases and 50 deaths. By Jan. 26, that number was down to 12 new cases and four deaths.

Hassler lifted the order altogether on Feb. 1, 1919, perhaps not coincidentally the day that the Anti-Mask League imploded at a final meeting. Harrington was voted out as chair. She protested the new chairwoman’s legitimacy, and the meeting ended in abrupt darkness.

“I rented this hall,” Anti-Mask League member William Scott said, “and now I’m going to turn off the lights.”

Peter Hartlaub is The San Francisco Chronicle’s pop culture critic. Email:phartlaub@sfchronicle.comTwitter:@PeterHartlaub