Justice Chambers (left) works on an espresso machine as partner Jenna Garrett takes an order from neighbor Walter Howell at their Soul Blends Coffee Roasters pop-up cart.

Stephen Lam/The ChronicleYou can’t escape the clang and grind of construction in West Oakland’s Clawson neighborhood. Three stories, four stories — new buildings sprout sleek live-work spaces, condos and market-rate apartments; grids of mustard, tomato-red and aluminum. On ground floors, white shells promise retail potential, chances for entrepreneurs to realize dreams and enhance the neighborhood.

Three-year-old Hollis Oak, a so-called “modern apartment community,” sits on Peralta Street, not far from a venerable urban farm and an encampment sharing awkward real estate at Fitzgerald and Union Plaza parks. There, a Clawson coffee hound finds an oasis: espresso, under a tent, courtesy ofSoul Blends Coffee Roasters.

隐形作为他的name, Shadow, the company dog, sidles over for a two-legged hug. You’re there for coffee, but you also can’t ignore the consequences of a changing neighborhood bottled in an intersection, crowned bythat powerful signifier, a drink the price of a sandwich.

Yet this is not a simplistic gentrification story. According to Justice Chambers, co-owner of Soul Blends, Hollis Oak replaced a junkyard, not family homes. Soul Blendsisstaking a claim of sorts, trying to maintain a profitable business at a timeparticularly challenging for minority entrepreneurslike Chambers and his partner, Jenna Garrett. At the same time, it’s also under a tent — there, roasting and selling, but not fully vested. Until Soul Blends can find a stable indoor location, ideally at Hollis Oak, the cafe will remain a perpetual pop-up.

A Soul Blends Coffee Roasters pop-up cart in the Clawson neighborhood of Oakland.

Stephen Lam/The ChronicleWhile the metal jazz quartet facade looming above Hollis Oak certainly contrasts with the encampment and even the nearby patched basketball court, the roster of artisans and entrepreneurs who live and work at Hollis Oak is racially diverse. The scene at the building’s recent pop-up market reflected Oakland’s demographics — as opposed to an influx of white home buyers.

Chambers makes another point: People should see young Black entrepreneurs staking out territory in such a historically privileged domain as high-end coffee. “If we don’t step in, others will,” Chambers says. Media figuresjokeabout Millennials wasting nest eggs on lattes, but coffee is something to savor, a reason to linger, a spark for conversation.

Why shouldn’t Clawson have a place for that? And why shouldn’t Soul Blends provide it?

A double espresso pours from an espresso machine at a Soul Blend Coffee Roasters pop-up in Oakland’s Clawson neighborhood.

Stephen Lam/The ChronicleSoul Blends brewed itself in the cloud of the first pandemic year. Holed up in Modesto, Chambers and Garrett, like many others, faced existential strain. A photographer who attended San Francisco’s Academy of Art, Chambers was a classroom aide. Garrett, who studied business at Cal State Stanislaus, worked at the courthouse. Quarantines and closures called for a shift in direction, respite from an old, unsatisfying churn.

“The pandemic gave us time to think,” says Garrett. And when they decided to roast and sell coffee beans, they thought of history — Oakland’s, Africa’s, their own.

“We wanted to honor our ancestry,” says Chambers. “You lose a lot with the past. Coffee can be a gateway to learning more about ourselves.”

Even as they search for a permanent location, Chambers and Garrett characterize their business as a reclamation of those roots, a reignition of frayed connections. It evokes Yaa Gyasi’s “Homegoing,” in which two branches of a bloodline separated by continents, slavery and colonialism reconvene centuries later. In the novel, home isn’t fixed; it’s a collection of ideas and feelings as portable as a steaming cup, something rediscoverable.

Justice Chambers (left) and partner Jenna Garrett place items into carts in their home for a Soul Blends pop-up in the Clawson neighborhood of Oakland.

Stephen Lam/The ChronicleIn early 2021, when Chambers and Garrett cruised Lake Merritt for possible spots, the couple saw a link between the scrappy local tradition of unregulated vending and African markets. They soon sourced beans from Tanzania and Ethiopia, partnering with Grand Paradé, the Bay Area distribution company founded by Kenya-born Kavi Bailey. The Oaklandish Coffee Collective at Oakland International Airport now sells their beans, usually roasted at home in a machine no bigger than a couple of shoeboxes, so travelers can take them anywhere their planes fly.

When Garrett and Chambers began dating eight years after attending the same high school, coffee was also a ubiquitous presence in their relationship. They’d drive into Oakland, get coffee and take photographs. Chambers was born in Berkeley, Garrett in Mendocino, and so they decided to move to the Bay Area, inspired by the coffee scene — especially Red Bay andother companies owned by people of color. Garrett knew business and Chambers had enjoyed making drinks at a bustling Financial District Specialties Cafe during his time in San Francisco. They first sold at Lake Merritt and then settled in at Hollis Oak in December 2021.

With waves of Black migrants after World War II, Black-owned businesses thrived in West Oakland, but that vitality didn’t last. “Hella Town,” a 2021 history of Oakland’s development by Mitchell Schwarzer, who teaches architectural and urban history at California College of the Arts, details, for instance, how BART construction and urban renewal initiatives “tore apart” the Seventh Street retail strip by the 1970s, and how, from 1960 to 1980, the number of West Oakland grocery stores declined by 84%. Hemorrhaging restaurants, jazz clubs and other local businesses, West Oakland lost vibrancy, but that’s perhaps changing with the likes of Matt Horn’sHorn Barbecueand even Soul Blends — for the people who can afford rent. On average,a one-bedroom apartmentin Clawson goes for $2,400.

Jenna Garrett, co-founder of Soul Blends Coffee Roasters, pulls carts of materials before setting up a pop-up outside Hollis Oak in the Clawson neighborhood of West Oakland.

Stephen Lam/The ChronicleAnd that’s the irony. Clawson was once dubbed “Dogtown” for its strays. Now, poodle mixes prance down the streets. “This ain’t the neighborhood that I grew up in,” longtime resident Dante Zedd told The Chronicle in2018for a story about gentrification in Clawson. “This is the neighborhood I wish I grew up in.”

Over at Horn, on Mandela Parkway, lines for brisket snake down the block. But barbecue is a destination, while coffee more easily becomes convenience. In March, Soul Blends lobbied to sell at the brand-new West Oakland Farmers Market that opened less than a mile away on Sunday, and until the end of May, weren’t aware they would be included. But now they’re booked for the first Sunday of every month. In May, Garrett and Chambers found out that, starting this week, they’ll also serve for a month at the nearbyPacific Pipe climbing gym— a third (albeit temporary) location. This is the rhythm of the scrappy startup business. Temporary and part-time opportunities arrive quickly, sometimes in bunches, and require a nimble response.

Earlier in the year, the duo’s dedication and drive caught the attention of Michelle Walton, co-owner of the Collective Oakland Bookstore. When Walton started theLoyal to the Soil Collectivein nearby Uptown, she envisioned an incubator for Black-owned businesses like Soul Blends. Companies would take over sections of the 2,000-square-foot space for 12-week stints. There, until late July, Soul Blends has yet another temporary location, a “pour-over bar.”

A latte by Soul Blends Coffee Roasters is seen during a pop-up outside Hollis Oak in West Oakland.

Stephen Lam/The Chronicle“We selected Soul Blends because of their passion,” Walton says. “Our goal is helping them secure a storefront of their own.”

Walton sees such collaboration as a home-grown solution to a problem disproportionately affecting minority-owned businesses. From April to August of 2020, almost 25% of businesses in the Clawson Census tractsreceived Paycheck Protection Program loans, compared with nearly 50% of businesses in Montclair. Parts of East Oakland topped out at 5%.

“在芝加哥,新奥尔良和奥克兰,epicenters for past migration of African Americans, businesses like ours congregate,” says Chambers, noting West Oakland’s history as well as Walton’s mission. “We can say, ‘hey, let’s help each other. Let’s do this.’ In other parts of the country, there aren’t as many resources for African Americans.”

“You can’t do it alone,” adds Garrett. “That goes back to our roots too.”

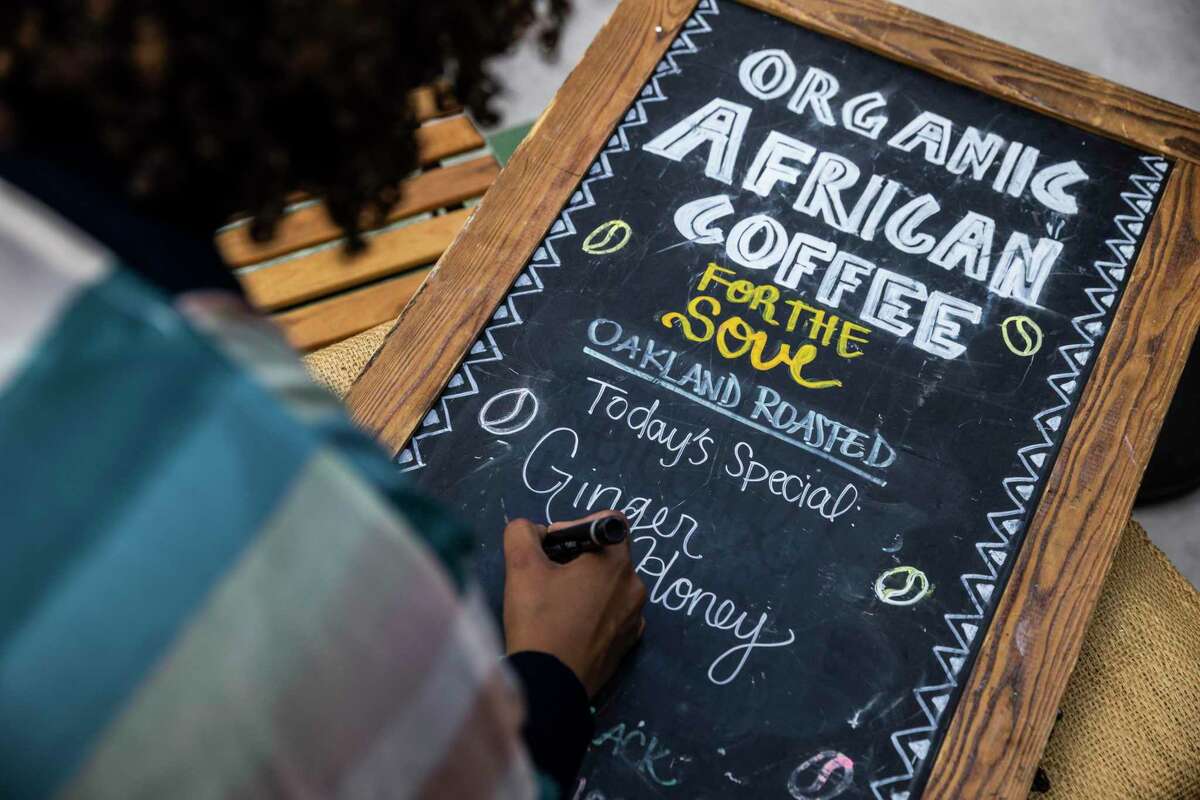

Jenna Garrett, co-founder of Soul Blends Coffee Roasters, writes the day’s specials on a board.

Stephen Lam/The ChronicleIn April, right before opening at Loyal to the Soil, Garrett and Chambers caught COVID-19. For a two-person operation, running two separate stands simultaneously was already tenuous math. But then an ultimately unsurprising thing happened. The couple shared their predicament on social media and community donations flooded in — enough to get them past a week of lost sales.

“It humbled us,” says Garrett. “When you have an amazing community, when everyone works together, you can survive.”

Andrew Simmons is a Bay Area freelance writer. Email:food@sfchronicle.com