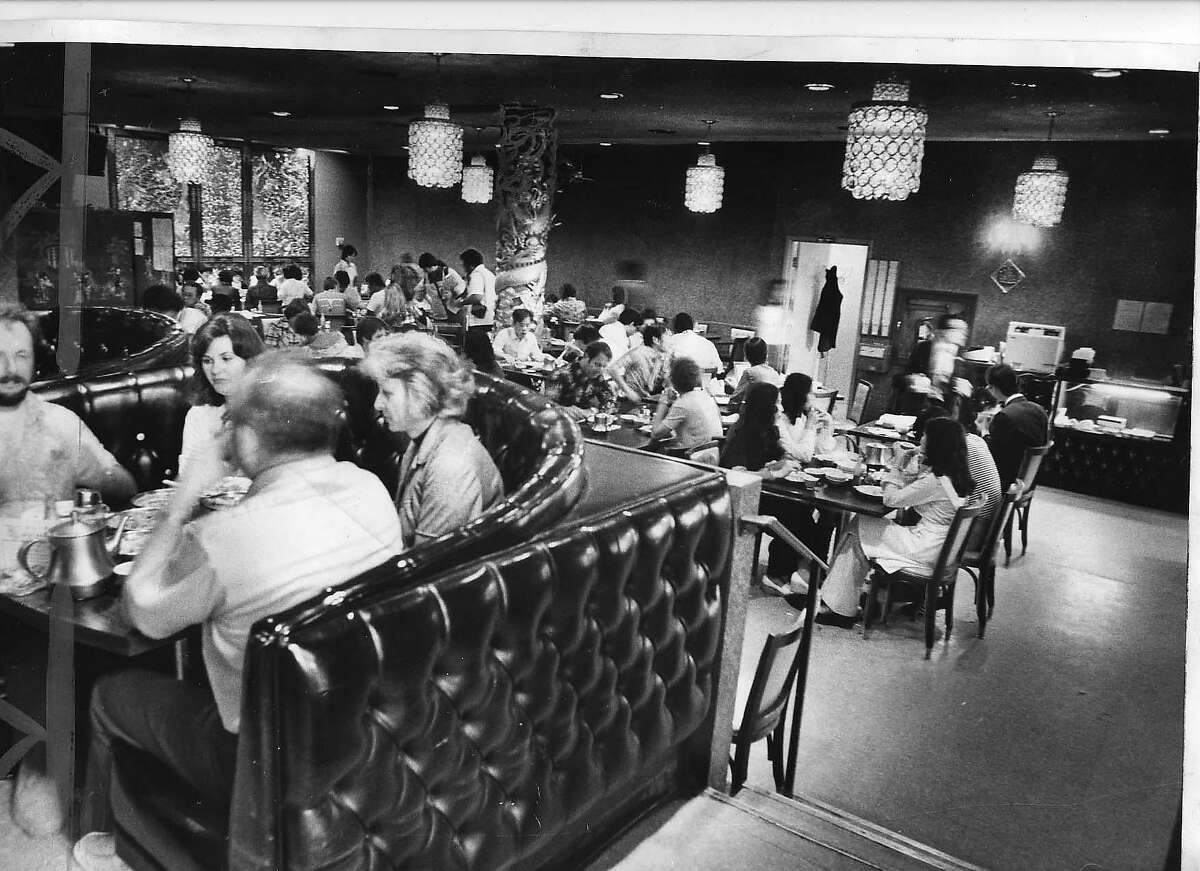

At 2:40 a.m. on Sunday, Sept. 4, 1977, the height of Labor Day weekend, the Golden Dragon Restaurant was bustling. Few Chinatown restaurants besides the cheap noodle joint Sam Wo across Washington Street were still open, and about 100 tourists and locals were seated at the restaurant’s two dining levels.

Among the diners were several leading members of the Chinatown underworld. One of them was a 20-year-old man named Michael “Hot Dog” Louie, head of a powerful gang called the Wah Ching. Louie and two friends were seated in a booth in the upper, mezzanine level, with other gang members dining nearby. Also in the restaurant was Frankie Yee, leader of another gang called the Hop Sing Boys.

One of the men in Louie’s booth, Wayne Yule Lee, looked out onto Washington Street and saw a man running past the window with a sawed-off shotgun, followed by a second man in a coat carrying a long-barrel shotgun. A third man, holding a semiautomatic rifle, looked in the window.

Lee yelled, “Man with a gun!” in Cantonese. Hot Dog Louie leaped across the aisle and ducked down as the three gunmen burst through the two sets of glass doors.

Innocent victims

The gunmen, wearing stocking masks, fanned out through the restaurant. The one with the rifle went to the main dining area. The two with shotguns went up three stairs to the mezzanine.

The gunman with the rifle swept his barrel across the room, looking for the men he had come to kill. When a young man at a table with three young women jumped in terror, the rifleman opened fire at the table. The other gunmen also began shooting wildly as patrons screamed and dove to the ground. The shooting lasted about a minute. The gunmen ran out of the restaurant, got into a car and barreled out of Chinatown.

The assassins left five people dead or dying. Eleven more lay wounded, several critically. As Brock Morris writes in his website, Bamboo Tigers, about the massacre, among the fatally shot was the man who had jumped, 25-year-old Paul Wada, a Japanese American law student at the University of San Francisco, and his friend Denise Louie, a 20-year-old Chinese American woman from Seattle.

Both Wada and Louie were bright young people who worked with the disadvantaged. Fong Wong, a 48-year-old waiter at the Golden Dragon who had emigrated from Hong Kong in 1969 and was a talented violin player and family man, was also killed, as were 18-year-old Calvin Fong and 20-year-old Donald Kwan, both hardworking, churchgoing youths who were starting classes at City College.

Longtime conflict

None of the victims had anything to do with Chinese gangs. They simply had the misfortune to be on the scene when the murderous tit-for-tat shootings that had plagued Chinatown for years exploded into one of the worst mass shootings in San Francisco’s history.

As Bill Lee writes in his 1999 book, “Chinese Playground: A Memoir,” the massacre at the Golden Dragon had its roots in a complex struggle between different gang and organized-crime factions in Chinatown.

The original rift, dating to the early 1960s, was between American-born Chinese, or ABCs, and new immigrants from Hong Kong who were derisively called FOBs, for Fresh Off the Boat. The native-born Chinese tormented the FOBs relentlessly, until the immigrants formed a gang called Wah Ching, or “Chinese Youth,” in 1964. The tables quickly turned.

“这些人长大的街道上的Kong and Macao where gangs were hardcore,” Lee writes. “Many had spent a good part of their youth in brutal prisons. This was now their Chinatown.” The Wah Ching would search out their enemies and brutally beat them.

This rivalry was soon swallowed up by a war that erupted between the powerful long-standing criminal syndicate that ran Chinatown, which Lee calls the Hock Sair Woey or Chinese Underground, and new gangs that challenged it. The most formidable of these gangs was formed by a former Wah Ching member named Joe Fong, who left the gang in 1971. In retaliation for his leaving, syndicate hitmen brazenly gunned down one of Fong’s best friends, Raymond Leung, chasing him through Chinatown and killing him at the corner of Jackson and Grant. In 1972, Fong formed his own gang, which came to be known as Joe Boys.

Origin of the massacre

A murderous series of tit-for-tat killings between the Wah Ching and its syndicate allies, primarily the Hop Sing Tong, and the Joe Boys began. (The Golden Dragon Restaurant was owned by Hop Sing Tong chief Jack Lee.) The war was driven both by the gangs’ desire to control the lucrative criminal trade in Chinatown and by simple vengeance. During the 1970s, close to 50 people were murdered — some of them chased through the streets of Chinatown and gunned down, some of them ambushed at home or work. One kid was abducted and brutally tortured before being killed.

Yet, convictions were hard to come by: A code of silence governed the terrified residents of Chinatown. Even spouses of murder victims would refuse to speak.

The incident that triggered the Golden Dragon massacre took place at the Ping Yuen housing projects on Pacific Avenue near Stockton Street. For years, the gangs had made large sums of money selling illegal fireworks out of the projects. The Wah Ching and their Hop Sing allies had long controlled the trade, but 8:30 p.m. on the Fourth of July, the Joe Boys tried to muscle in. But they botched the assault — partly because they couldn’t find a place to park — and the Wah Ching were ready.

“It was Dodge City in Chinatown,” Lee writes. “Weapons were drawn and gunfire erupted, with gangsters running up and down the street, ducking behind cars and into doorways, blasting at one another.” A 17-year-old Joe Boy named Felix Huey was shot to death in a Ping Yuen stairwell. Two months later, the Joe Boys struck back at the Golden Dragon.

City cracks down

The massacre marked the beginning of the end of the violent heyday of Chinatown’s gangs. The city created a Gang Task Force to work in Chinatown, the first since the famous “Chinatown Squad” of the early 20th century. Painstaking police work — and an unprecedented $100,000 reward, which was paid out to an informant — resulted in the apprehension and conviction of the three gang killers and their accomplices (except for the getaway driver, who was never apprehended). The Joe Boys disbanded.

And while the Chinese underworld still exists, its crimes are largely confined to extortion, gambling and prostitution. The days when gang enforcers chased their victims through the streets of Chinatown and gunned down innocent people in restaurants are over.

Gary Kamiya is the author of the best-selling book “Cool Gray City of Love: 49 Views of San Francisco,” awarded the 2013 Northern California Book Award in creative nonfiction. All the material in Portals of the Past is original for The San Francisco Chronicle. Email:metro@sfchronicle.com

Trivia time

Previous trivia question:Who was known as “the rudest waiter in the world”?

Answer:Edsel Ford Fong, who worked upstairs at Sam Wo.

This week’s trivia question:Where did some 49ers send their shirts to be laundered?

Editor’s note: