This is a carousel. Use Next and Previous buttons to navigate

Every year, throngs of people take “Vertigo” tours in San Francisco, visiting the sites whereAlfred Hitchcock shot his 1958 masterpiece.许多建筑物,如豪华Brocklebank apartments atop Nob Hill and the building at 900 Lombard St. where James Stewart’s character lives, still stand.

But one location, a Victorian mansion whose name in the film is the McKittrick Hotel, has vanished. It did not disappear without a trace, however. Its story — revealed here in full for the first time — is as bizarre and disquieting as Hitchcock’s story of obsession and identity.

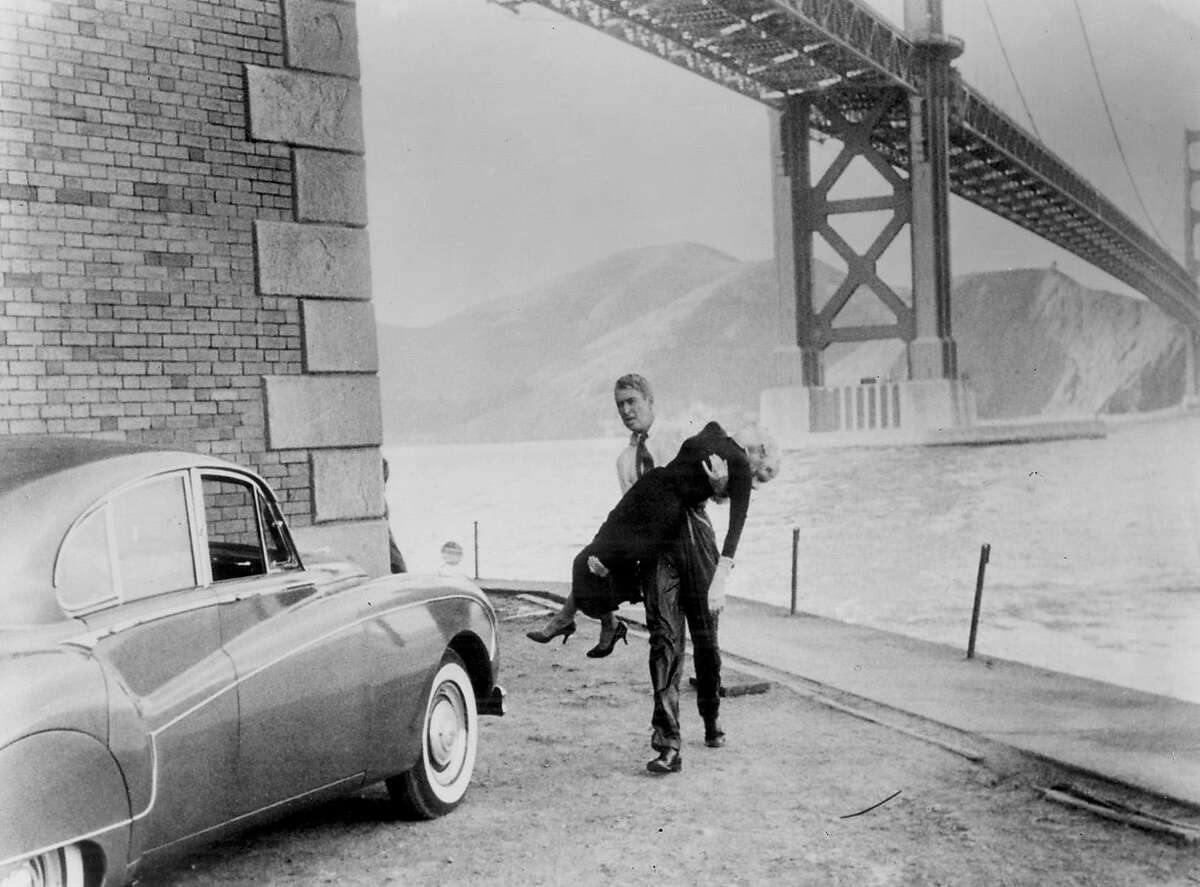

The scene that takes place in the McKittrick Hotel is very weird — Hitchcock scholar Donald Spoto calls it “perhaps the strangest moment in the film.” Madeleine Elster, the mysterious woman played by Kim Novak, has just left the Mission Dolores cemetery, where she has communed with the grave of Carlotta Valdes, a 19th century ancestor who supposedly has taken possession of her.

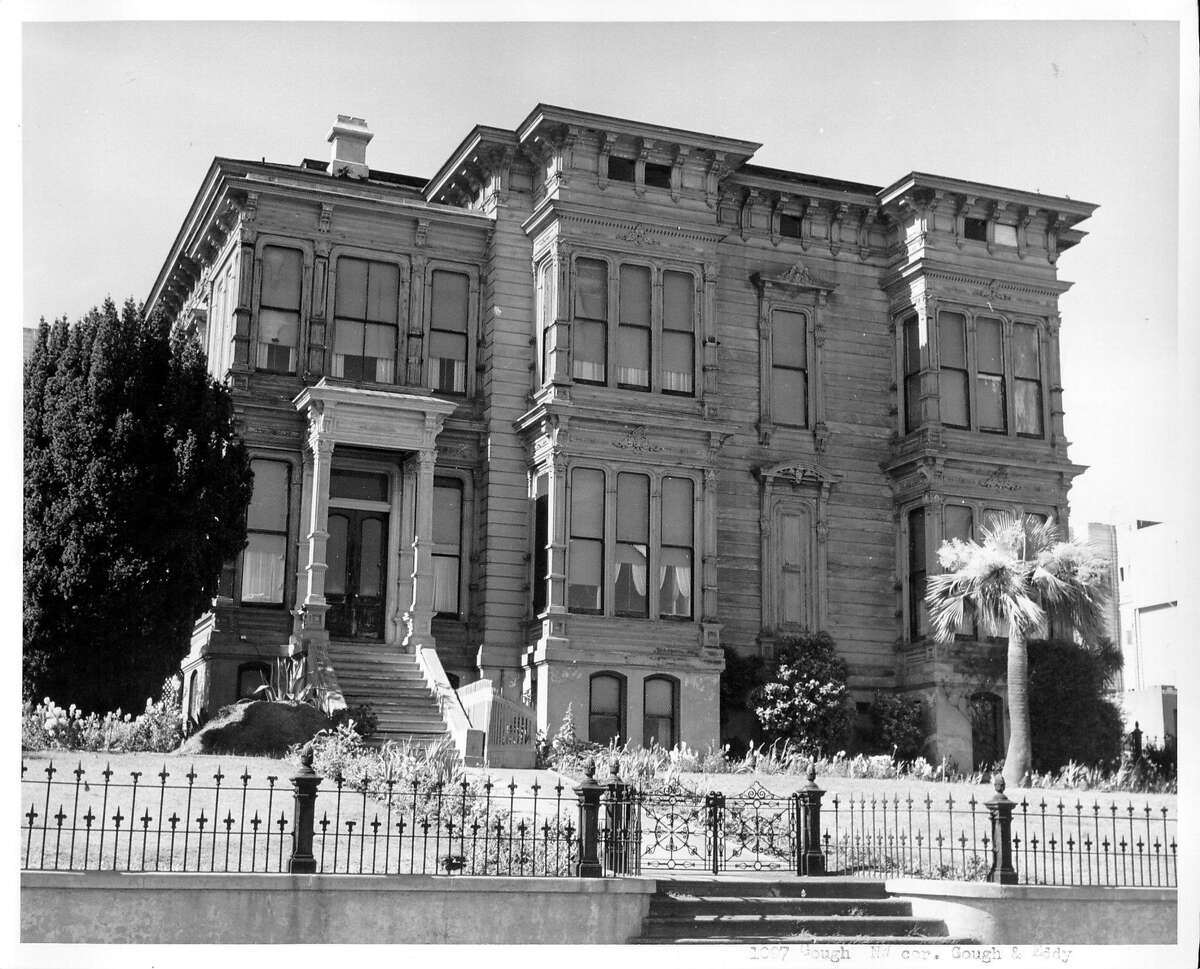

Madeleine drives away, trailed by detective John “Scottie” Ferguson (Stewart), who has been hired to keep an eye on her. After visiting the Palace of the Legion of Honor, Madeleine drives across town to a slightly run-down, vaguely creepy Victorian bearing a small sign identifying it as the McKittrick. Madeleine walks in. A few moments later, we see her in an upstairs window.

Scottie walks into the foyer and asks who lives in the corner room on the second floor. Miss Valdes, the manager replies.

Scottie says, “When she comes down, don’t say that I’ve been here.” But as he turns to go, the manager stops him short by saying, “Oh, but she hasn’t been here today.” She explains that no one could have gone up the stairs without her noticing, then leads him to the empty room.

Looking out the window, Scottie says, “Her car is gone.” The manager replies, “What car?”

What happened to Madeleine at the McKittrick Hotel is never explained. Did she somehow slip out? Was the whole incident Scottie’s hallucination? Or did Hitchcock simply suspend the laws of reality? We don’t know.

The episode is an example of what Hitchcock called an “icebox talk scene,” a narrative conundrum that he slipped into his films to give audiences something to talk about as they rummaged through the refrigerator after the movie.

The master of suspense almost certainly didn’t know the strange history and dismal fate of that creepy mansion. If he had, he might have been inspired to make a thriller about it — perhaps titled, “The House Vanishes.”

Previous trivia question:What San Francisco restaurant featured 100 kinds of hamburger?

Answer:The Hippo, at Van Ness and Pacific

This week's trivia question:What was the original use of the building that now houses the Maritime Museum at Aquatic Park?

Every corner in San Francisco has an astonishing story to tell. Gary Kamiya's Portals of the Past tells those lost stories, using a specific location to illuminate San Francisco's extraordinary history - from the days when giant mammoths wandered through what is now North Beach to the Gold Rush delirium, the dot-com madness and beyond. His column appears every other Saturday, alternating with Peter Hartlaub's OurSF.

Like what you're reading? Subscribe to theChronicle Vault newsletterand get classic archive stories in your inbox twice a week.

Read hundreds of historical stories, see thousands of archive photos and sort through 153 years of classic Chronicle front pages atSFChronicle.com/vault.

The building’s story begins in 1879, when an old-timer named John Conly built the 18-room Victorian on the northwest corner of Eddy and Gough streets, in the newly developing Western Addition. Conly, or “Old John” as he was called, was well known throughout the state. After opening a general store in the Plumas County town of La Porte in the 1860s, he co-founded the Bank of Chico and later served as a state senator for Plumas and Butte counties.

But Conly’s sons, John and William, turned out to be ne’er-do-wells. After Old John died in 1883, they burned through his entire $400,000 estate and left his widow, Emma, penniless. According to an 1894 story in The Chronicle, the sons habitually wrote large checks on their mother’s bank account, which she was too proud to decline until she had nothing to her name but her husband’s watch.

With no more inheritance to sustain him, John turned to fraud. He was arrested in April 1894 for swindling a Berkeley woman out of $8,500, promising her he would invest it in land. After jumping bail, he was reportedly seen “roaming about in the interior.”

The house he grew up in did not remain in his family long after his arrest. In December 1895, The Chronicle reported that the “principal event in the local real estate market this week” was the sale of the “old Captain Connolly” (sic) mansion to a San Francisco businessman named Henry F. Fortmann.

The 39-year-old Fortmann purchased the building and its lot for $42,500 — about $1.5 million today — from the Bank of California, which apparently had repossessed the property from the Conly estate. “The price is considered low by the seller,” The Chronicle reported. “The building is a substantial structure, containing 18 rooms. It will be modernized by its new owner, who will reside in it while waiting for the remainder of the lot to rise in value.”

If the Conly saga was a familiar San Francisco tale of squandered wealth and familial decline, the Fortmann saga was an equally classic immigrant success story.

Fortmann’s father was a German named Frederick F. Fortmann, who immigrated with his wife to San Francisco in 1852. That year he started one of San Francisco’s first breweries, the Pacific Brewery at Fourth and Tehama streets.

In 1859, the elder Fortmann became a founding member of the German American Shooting Society, one of the many ethnic-solidarity organizations that sprang up in the city’s early days. In 1934, to accompany a story on the group’s 75th anniversary, The Chronicle ran a photograph taken at the group’s very first shoot. It shows six rifle-holding German immigrants and a small child. One of the men is Frederick Fortmann. The child is his 2-year-old son, Henry.

By the time of the 1934 story, Henry Fortmann was the group’s oldest member. He had joined with other investors in creating a fruit-canning monopoly, then became president of the Alaska Packers Association, making a fortune in the salmon-canning trade. He held membership in 26 societies and clubs, including the Bohemian, Olympic and Pacific Union clubs.

He and his wife, Julia, raised their two daughters in that 18-room Victorian at Eddy and Gough. Both daughters were married there.

By 1945, however, Henry Fortmann was a widower and the once-swanky neighborhood was in decline. He moved out of the house he had bought a half-century earlier and into the Pacific-Union Club atop Nob Hill, and died the next year at age 89.

By this time, the Victorian mansion had seen many plot twists. Its final chapter would prove to be the strangest of all. That story will appear in the next Portals.

Gary Kamiya is the author of the best-selling book “Cool Gray City of Love: 49 Views of San Francisco,” awarded the Northern California Book Award in creative nonfiction. All the material in Portals of the Past is original for The San Francisco Chronicle. To read earlier Portals of the Past, go towww.batsapp.com/portals. For more features from 150 years of The Chronicle’s archives, go towww.batsapp.com/vault. Email:metro@sfchronicle.com