This is a carousel. Use Next and Previous buttons to navigate

The biggest fan of early San Francisco’s celebrated volunteer firefighters, and one of the great free spirits in the city’s history, was a transplanted Southern belle named Lillie Hitchcock Coit.

“Lillie Hitchcock Coit is the most original woman California has produced,” The Chronicle wrote in 1895. Even though the field at the time contained competitors like Lotta Crabtree, Mary Ellen Pleasant, Fanny Stevenson and Juana Briones, there’s a case to be made for The Chronicle’s choice. Coit’s long life had as many twists and turns as any battle against a raging conflagration ever fought by her beloved firemen.

She was born to a well-to-do Southern family in 1843; her Virginian father became wealthy as a physician in San Francisco after serving as an Army doctor in the Mexican-American War. According to Doris Muscatine in “Old San Francisco,” Coit’s mother, Martha, never gave up her ties to the Old South, and in 1850 burned down her own family plantation in North Carolina rather than see it fall into the hands of squatters after she lost financial control of it. Coit would inherit her mother’s passion for the Southern cause.

There are two versions of how Coit fell in love with San Francisco’s volunteer fire companies. According to Muscatine, not long after the Hitchcock family moved to San Francisco in 1851, 8-year-old Lillie and some playmates were exploring an old ruined building when it caught fire. The children were trapped, but a volunteer member of Knickerbocker Engine Company No. 5 cut through the roof, lowered himself on a rope and carried Lillie to safety. Two of her friends didn’t make it out. After that, every time Lillie saw No. 5 rushing to a fire, she would run after them and help them pull their engine.

The other version is that Lillie simply saw Knickerbocker 5 racing to a fire and joined in.

Whichever story is correct, Coit conceived a lifelong passion for the Fire Department in general, and No. 5 in particular. Over the objections of her parents, she answered every alarm that No. 5 answered. The firemen, in turn, adopted little Lillie as a mascot and gave her a gold badge, which she never took off.

Lillie’s parents tried to rein her in, but she was irrepressible. She was engaged no fewer than 15 times, at one point to three men, all naval officers, simultaneously. She hung out in back rooms with male friends, smoking cigars, drinking bourbon and playing poker expertly. She is said to have sneaked into the all-male Bohemian Club’s High Jinks dramatic performance by disguising herself as a man.

She drove a team at breakneck speeds. She would coolly wager a thousand dollars on a favorite horse, and rode on the cowcatcher of the Napa Valley Railroad for its entire line to win a bet. According to The Chronicle, “She kept San Francisco society in a whirl, alternately smoothing it down and shocking it into insensibility.”

All the while, her passion for chasing fires remained unabated. One night she was attending a performance at the California Theater on Bush Street, with the orchestra under the baton of Charlie Schultz, who was a volunteer firefighter. Suddenly the fire bell rang. As The Chronicle reported, “Charlie dropped fiddle and bow and made a rush for the orchestra door. Just as he gained it, flop! From the box above dropped Lillie Hitchcock, and flung her arms around his neck. “Me too, Charlie!” she lilted; and amid the uproarious cheers of the audience, they vanished.”

Coit divided her time between San Francisco and Paris, where she was a regular at the court of Napoleon III and Empress Eugenie and cut a dazzling figure at the balls. Her dance card was always full, and her suitors marveled at the embroidered “Five” among the ruffles of her opulent gowns.

臀部对南方的热情导致在Civil War led her to undertake a number of secret missions, including smuggling a rebel aboard a U.S. Navy ship and carrying confidential papers to the Confederacy. However, her sympathies did not lead her to waver in her commitment to Knickerbocker 5, whose New Yorkers were pro-Union. When she returned to San Francisco at age 20, Knickerbocker 5 gave her a certificate of honorary membership, making her the only honorary female member of a fire department in the country.

Although she was the most sought-after belle in San Francisco, Lillie was romantically interested in only one man, Howard Coit, the caller at the stock exchange and a noted bon vivant. Lillie’s parents considered him a fortune hunter, and when the young couple eloped, they disowned her. They later reconciled, however, and Lillie’s parents ended up living as neighbors to Lillie and Howard in the Palace Hotel.

Every corner in San Francisco has an astonishing story to tell. Gary Kamiya's Portals of the Past tells those lost stories, using a specific location to illuminate San Francisco's extraordinary history - from the days when giant mammoths wandered through what is now North Beach to the Gold Rush delirium, the dot-com madness and beyond. His column appears every other Saturday.

Like what you're reading? Subscribe to theChronicle Vault newsletterand get classic archive stories in your inbox twice a week.

Read hundreds of historical stories, see thousands of archive photos and sort through 153 years of classic Chronicle front pages atSFChronicle.com/vault.

Lillie and Howard had a rocky marriage and eventually separated. But Howard’s sudden death at age 47, not long after the death of Lillie’s father, sank Lillie into a deep depression. When she emerged, her behavior became increasingly eccentric. She entertained friends at a feverish pitch and raced from Paris to Hawaii and back to San Francisco.

At the age of 57, she shocked the entire country by staging a private boxing exhibition in her rooms at the Palace between two middleweight champions. As Muscatine writes, “Aghast at her daring, yet admiring the freedom of spirit that allowed San Franciscans to take her in stride, the writers wondered if her independence did not augur a new era for woman.”

Three years later, a distant cousin named Garnett barged drunkenly into her suite and opened fire, killing her financial adviser. Coit testified against Garnett, who vowed to kill her when he was out of jail. She fled the city and traveled the world for more than 20 years, returning only when Garnett died in a mental institution in 1923.

On July 22, 1929, Lillie Hitchcock Coit died at the age of 88. At her funeral at Grace Cathedral, 22 firefighters attended as representatives of the Fire Department, as well as three old gentlemen who had been volunteer firemen for various companies and had known Lillie in her youth. When she was cremated, she was wearing, as always, the gold pin of No. 5.

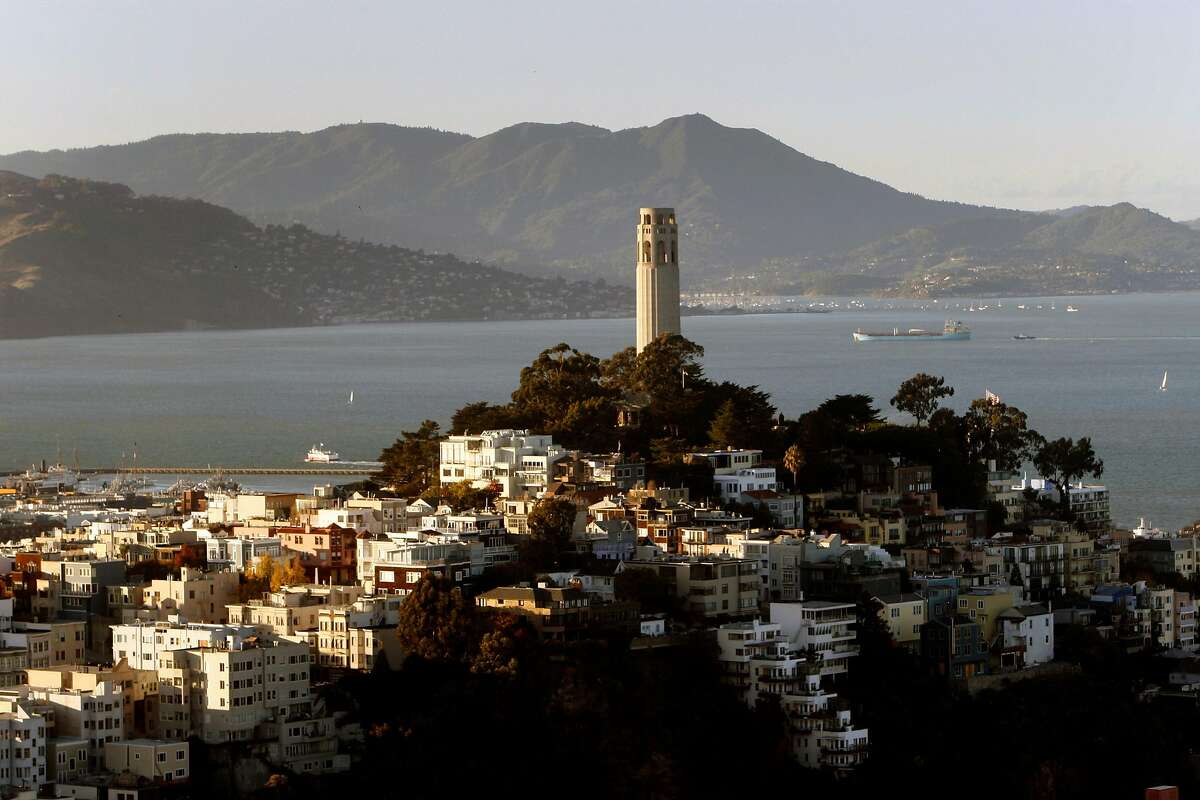

In her will, Coit specified that $100,000 be used for the beautification of San Francisco. City officials and her heirs decided to build two memorials: 170-foot Coit Tower atop Telegraph Hill, and the monument to the city’s volunteer fire companies in Washington Square. Those two monuments, located within sight of each other, ensure that the memory of one of the city’s most beloved originals will endure.

加里Kamiyais the author of the bestselling book “Cool Gray City of Love: 49 Views of San Francisco,” awarded the Northern California Book Award in creative nonfiction. His new book, with drawings by Paul Madonna, is “Spirits of San Francisco: Voyages Through the Unknown City.” All the material in Portals of the Past is original for The San Francisco Chronicle. To read earlier Portals of the Past, go tosfchronicle.com/portals. For more features from 150 years of The Chronicle’s archives, go tosfchronicle.com/vault. Email:metro@sfchronicle.com