This is a carousel. Use Next and Previous buttons to navigate

From the Gold Rush days to almost the turn of the 20th century, the weirdest bar in San Francisco, if not the world, was in a dilapidated building on the waterfront in North Beach. It was known as Abe Warner’s Cobweb Palace, and its like will never be seen again.

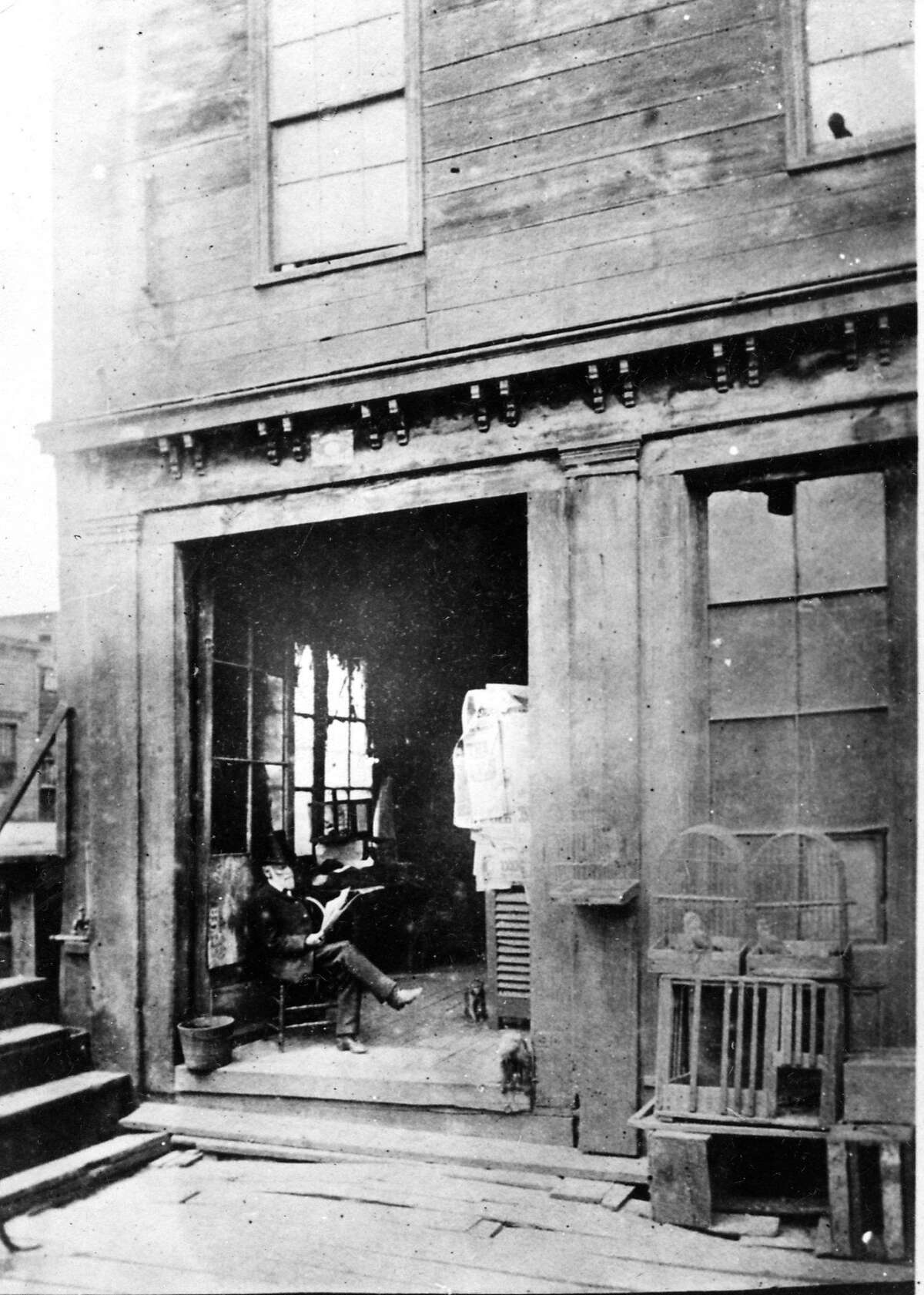

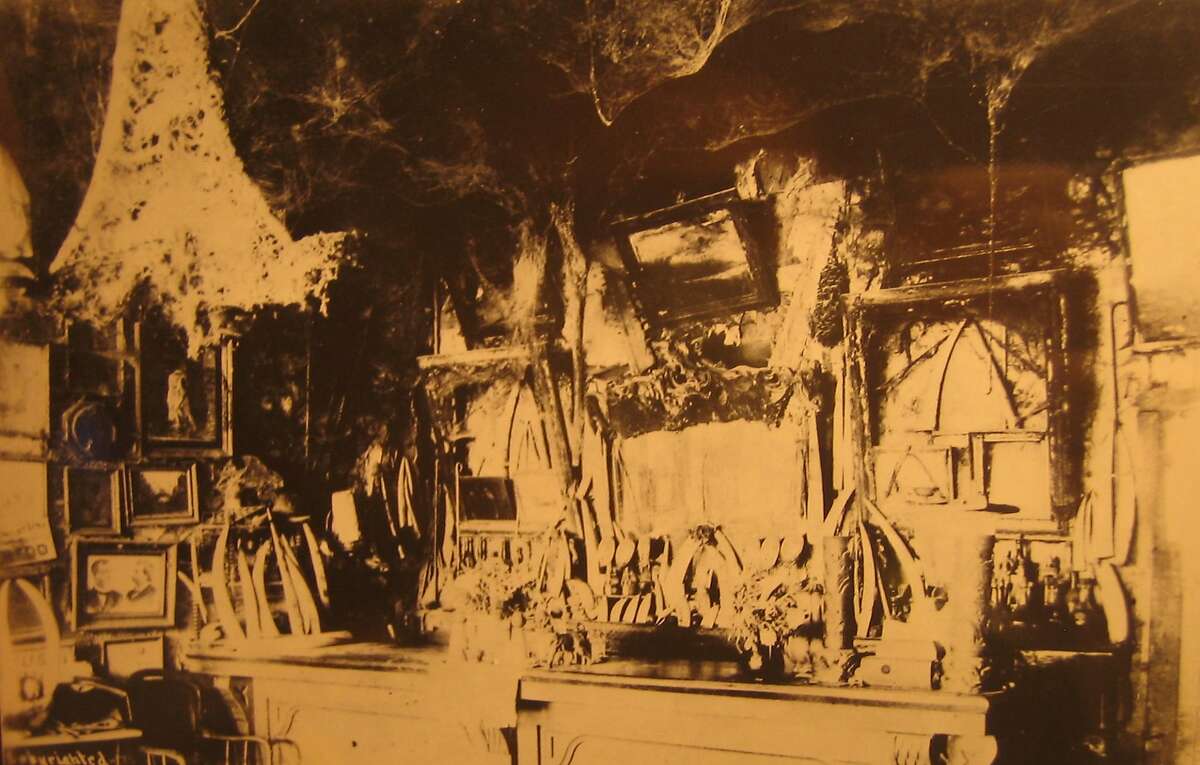

The Cobweb Palace, on Francisco Street near the site of today’s North Beach Malt House, was named after its most notable feature: a thick forest of spider webs that covered its ceiling and much of its walls, and hung so low that they brushed against the hats of tall men. According to an 1893 story in the Examiner, soon after acquiring the saloon in 1856, Warner asked his landlord for a lease. When the landlord refused, Warner vowed, “Then I’ll be tarred if I fix or clean the place till you do.”

He was true to his word. For 37 years, no broom was ever used inside Warner’s saloon.

But the cobwebs were not the only strange thing about Warner’s saloon. It was also a veritable menagerie. Monkeys and baboons hung by their tails from projecting beams and roamed freely through its dim interior, next to dozens of white cockatoos and parrots, dogs and roosters. Outside the saloon, mountain lions, bears, coyotes and other wild animals were caged.

Every corner in San Francisco has an astonishing story to tell. Gary Kamiya's Portals of the Past tells those lost stories, using a specific location to illuminate San Francisco's extraordinary history - from the days when giant mammoths wandered through what is now North Beach to the Gold Rush delirium, the dot-com madness and beyond. His column appears every other Saturday.

Like what you're reading? Subscribe to theChronicle Vault newsletterand get classic archive stories in your inbox twice a week.

Read hundreds of historical stories, see thousands of archive photos and sort through 153 years of classic Chronicle front pages atSFChronicle.com/vault.

Completing the trifecta of oddness, the Cobweb Palace boasted what was undoubtedly the most stupendous collection of curiosities ever assembled in a saloon. Pride of place went to Warner’s collection of scrimshaw, which the Examiner described as “probably the greatest ever gathered. It represented all that was strange and beautiful in that line that had been brought to the port during nearly 50 years.”

Sailors knew that Warner collected carved ivory and bone pieces, and would bring treasures they had gathered from across the seven seas to sell to him. Mammoth tusks carved with hunting scenes and with images of Polynesian chiefs, and bone spears from the Aleutian islands, rubbed dusty shoulders with fragments of Indian canoes, a giant stuffed frigate bird and war clubs from the Fiji islands.

Warner also collected paintings, which the Examiner characterized as “mainly of a highly sensuous order of art, in which the predominant features are rounded limbs of well-formed but poorly clad females.” Fortunately for prudish sensibilities, the paintings were so grimy it was usually impossible to see what they depicted.

除了这些奇怪的景点,美食and strong drinks, the Cobweb Palace’s location ensured its success.

这是早期的脚附近圣法郎isco’s most celebrated structures, Meiggs’ Wharf. Constructed from 1852-53, the wharf started on Francisco Street between Mason and Powell and extended an impressive 1,900 feet into the bay.

Meiggs’ Wharf became the most popular destination for a Sunday outing in San Francisco. Those who stopped in at the Cobweb Palace for a free cup of Warner’s clam chowder and a hot toddy were greeted by a rusty green parrot chirping its famous line, “I’ll have a rum and gum. What’ll you have?” Children were entranced by the bears and mountain lions and would feed them peanuts, which they bought from a disabled sailor who hung around the joint.

The Cobweb Palace was the most popular tavern in town through the 1860s. Warner became a familiar character in his sober black suit and top hat, and the Cobweb Palace appealed to every class of citizen, from sailors to preachers to rakes to connoisseurs of natural history. Warner was taking in $50 to $100 a day, a fortune then.

But in the 1870s, the Cobweb Palace began to fall on hard times. Meiggs’ Wharf became less and less of a wharf, thanks to landfill that moved inexorably north. Heavy industry moved into the neighborhood. Other pleasure resorts like Woodward’s Gardens opened. As business dwindled, Warner was barely able to feed his monkeys and birds. In 1873, his creditors forced him to sell his most valuable pieces at auction. The end of “the highly decorated old rum shop,” as The Chronicle called it, seemed only a matter of time.

But the 65-year-old Warner refused to give up. The Cobweb Palace was his life. He had always slept in the old building. Sometimes he even caught his dinner there by prying up a board behind the bar and dropping a fishing line in the water. And so for 20 more years, he kept running the tavern, for himself and a shrinking band of old-timers, even though he was lucky to make $1 a day.

The end came in 1893, when the building’s owner decided to tear it down and build a malt house. A final auction raised $100; a grimy old piano sold for 25 cents.

An Examiner reporter who visited that day found Warner philosophical. “I’ve been expecting it for a long time,” he told a group of commiserating pioneers. “The old place is something like myself — I’m 85 years old, you know — it can’t hold together much longer. It’s like most of the old California houses — here a board and there a board, muslin tacked over the inside and the dust over everything. Look at the cobwebs — they’re beginning to fall with their own weight. It’s the same with all of us.

“I’ve got a place to fall, too,” he explained with a show of satisfaction. “Out of all the wreck of the great days, I’ve a bit of land in Odd Fellows Cemetery, 18 x 19. Not much to be sure, but plenty big enough for me. I’ll have company, too. There was Tom and Jack and Jim. They were good boys and they made big piles in their day, but they died flat busted and didn’t have a hole to crawl into. I buried them out in my plot; now they’ll be company for me.

“Though I don’t know,” the old man spoke slowly and dreamily. “I’d sort of like to be laid away here, right here and let the walls fall over me — old Cobweb Palace.”

After the building was demolished, Warner moved into a hovel at 406½ Francisco St., just steps away from the site of his beloved saloon. There he died, three years later, at the age of 88. The newspapers noted that his shabby room was as full of cobwebs as the tavern he had run in the days when the city was young.

Gary Kamiya is the author of the bestselling book “Cool Gray City of Love: 49 Views of San Francisco,” awarded the Northern California Book Award in creative nonfiction. His new book, with drawings by Paul Madonna, is “Spirits of San Francisco: Voyages Through the Unknown City.” All the material in Portals of the Past is original for The San Francisco Chronicle. To read earlier Portals of the Past, go tosfchronicle.com/portals. For more features from 150 years of The Chronicle’s archives, go tosfchronicle.com/vault. Email:metro@sfchronicle.com