This is a carousel. Use Next and Previous buttons to navigate

For almost 50 years, a San Francisco newspaper reporter who wrote under the pen name Annie Laurie touched the hearts of thousands of readers. Winifred Sweet’s fearless exploits and daring exposés made her one of the most celebrated female journalists of her day.

The future star reporter was born in Wisconsin in 1863 and was educated in Chicago. She failed to make it on the stage in New York, but another career opened after the editor of the Chicago Tribune published a letter she’d written to her sister describing the misadventures of an ambitious young actress.

In 1890 she went west to track down a younger brother who had run away and got a job at William Randolph Hearst’s San Francisco Examiner. Her first reporting assignment was to cover a flower show— typical of the stories given to the handful of women working in journalism at the time. But Sweet would not remain on the flower beat for long.

The 27-year-old Hearst, who became publisher in 1887, had transformed the formerly moribund Examiner into a brash, hard-hitting newspaper that blended sensationalism, aggressive reporting and an unabashed appeal to the masses. Hearst aspired to make the Examiner the West Coast version of Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World, the pioneer in the punchy, attention-getting, down-market style that would become known as yellow journalism.

The Examiner’s managing editor, Sam Chamberlain, told Sweet to “write for the gripman on the cable car.” She took the advice to heart, developing a simple but powerful style. She adopted a nom de plume, Annie Laurie, after her mother’sfavorite lullaby.

Like Pulitzer’s Nellie Bly, Sweet became a master of so-called stunt journalism, disguising herself and going to extraordinary lengths to get stories. Her breakthrough article was an 1890 exposé of the city’s emergency hospital services. She wore a shabby dress, put belladonna in her eyes and pretended to collapse on Kearny Street. Two unsympathetic policemen dragged her to a police wagon (the city had no ambulances), which carried her on a jolting ride to the receiving hospital in the basement of City Hall.

At the hospital, where she was listed as “hysterical,” a doctor and matron tried to force an emetic down her throat. Sweet wrote that as she struggled, another “dark, saturnine” doctor entered and, laughing, told them, “Give her a good thrashing and she’ll take it.”

When informed that “she says her head hurts,” the doctor replied, “She does, does she?” gripped her neck with both hands and thrust his fingers hard below her ears on each side.

When she screamed and managed to push him aside, the doctor seized her shoulder so hard he tore the skin, threw her on the bed and said, “Let her lie there, and if she makes any fuss, strap her down.”

The next day another Examiner reporter interviewed the physician, identified as Dr. Harrison. In the Page One story, Dr. Harrison said he had treated Sweet appropriately: Hysterical women all faked their symptoms, he said, and they needed either an emetic or a thrashing, “any treatment to give them something else to think about.”

Like what you're reading? Subscribe to theChronicle Vault newsletterand get classic archive stories in your inbox twice a week.

Read hundreds of historical stories, see thousands of archive photos and sort through 153 years of classic Chronicle front pages atSFChronicle.com/vault.

Every corner in San Francisco has an astonishing story to tell. Gary Kamiya's Portals of the Past tells those lost stories, using a specific location to illuminate San Francisco's extraordinary history - from the days when giant mammoths wandered through what is now North Beach to the Gold Rush delirium, the dot-com madness and beyond. His column appears every other Saturday.

After the story ran, Dr. Harrison was fired. Two days later he stormed into the Examiner’s office and picked a fight with an editor.

“But the city editor of the Examiner was not a sick female patient and the belligerent doctor’s attempt at bullying was a signal failure,” the Examiner reported. “After he had received a couple of punches in the face Dr. Harrison lay on his back whimpering like a whipped cur.”

Sweet’s story created a furor — and it got results. An ambulance service was created, and the city opened its emergency hospital system a few years later.

1892年,甜蜜的独家采访President Benjamin Harrison, reportedly by hiding under a table on his campaign train. She reported on the leper colony on Molokai island in Hawaii and penned a heartrending story about a disabled boy, “Little Jim,” who was born to a prostitute at the city hospital.

The intrepid young reporter had a special relationship with Hearst. He had complete confidence in her, and she, in turn, described him as “the strongest influence in my life” and “the simplest-hearted, wisest, most understanding, most forgiving, most encouraging human being it has ever been my luck to know.”

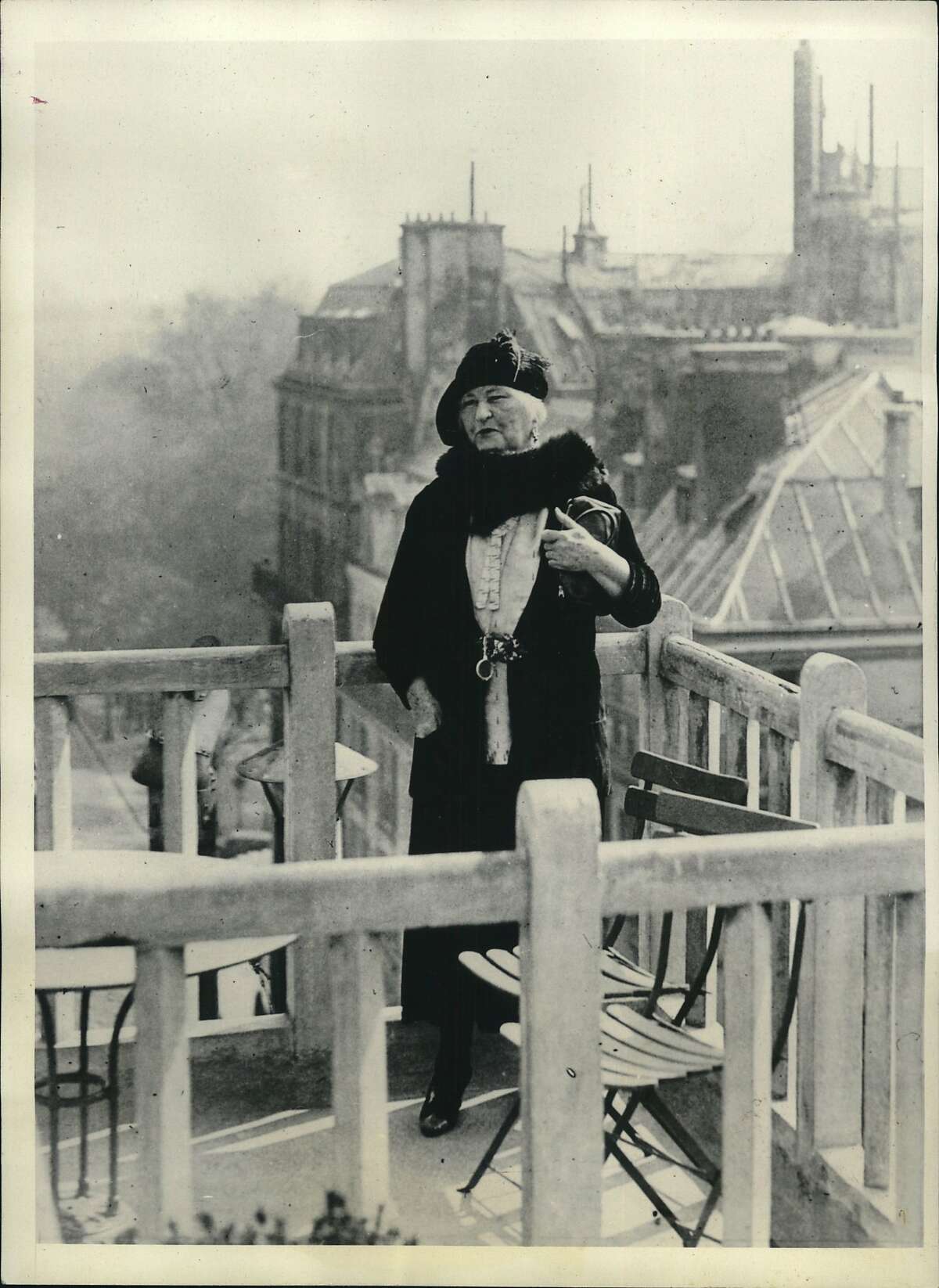

When Hearst challenged Pulitzer for East Coast newspaper supremacy by acquiring the New York Journal, he took Sweet with him. But she didn’t like New York and returned to San Francisco, and after a time got a job at the Denver Post.

虽然不是赫斯特纸后,甜蜜的反对tinued to write for him as well. Her greatest scoop came when she disguised herself as a boy to get through police lines and became the first outside journalist to enter Galveston, Texas, after the hurricane of September 1900 killed 7,000. She covered the 1906 earthquake and fire in her beloved San Francisco after receiving a telegram from Hearst that read simply, “Go.”

The next year, Sweet was one of four well-known female reporters at the murder trial of Harry Thaw, who shot architect Stanford White in a restaurant atop Madison Square Garden over White’s relationship with Thaw’s wife. Their sympathetic coverage of Thaw led cynics to call them “sob sisters.” Sweet hated the label, but it stuck and she was often referred to as the “greatest sob sister of them all.”

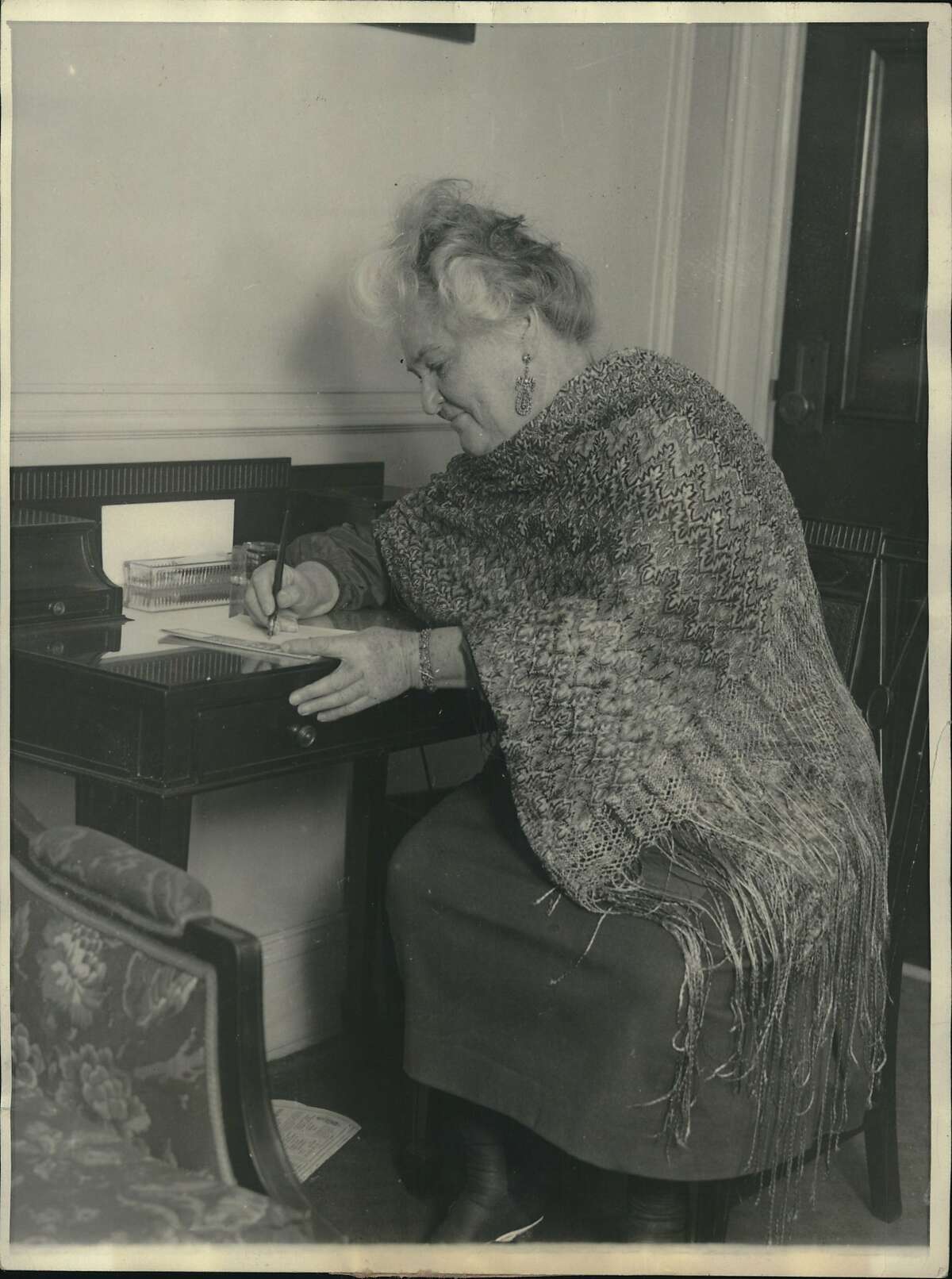

Sweet remained a newspaperwoman to the end. “I’d rather smell the printer’s ink and hear the presses go ’round than go to any grand opera in the world,” she once said.

Her death in 1936 at her home in the Marina was Page One news not just in the Examiner, but in the rival Chronicle as well. At the order of Mayor Angelo Rossi, her body lay in state in the rotunda of City Hall, the only journalist ever to be so honored.

Thousands of people, many weeping, came to pay their last respects to one of the most colorful and dauntless reporters in the city’s storied journalistic history.

A special note: I’m working on a piece on the Gold Rush-era soprano Elisa Biscaccianti. If anyone has information about her, please contact me at gary.kamiya@gmail.com.

Gary Kamiya is the author of the best-selling book “Cool Gray City of Love: 49 Views of San Francisco,” awarded the Northern California Book Award in creative nonfiction. All the material in Portals of the Past is original for The San Francisco Chronicle. To read earlier Portals of the Past, go tosfchronicle.com/portals. For more features from 150 years of The Chronicle’s archives, go tosfchronicle.com/vault. Email:metro@sfchronicle.com