Four dams on the Klamath River, as seen in May, are planned for removal in Northern California and Southern Oregon.

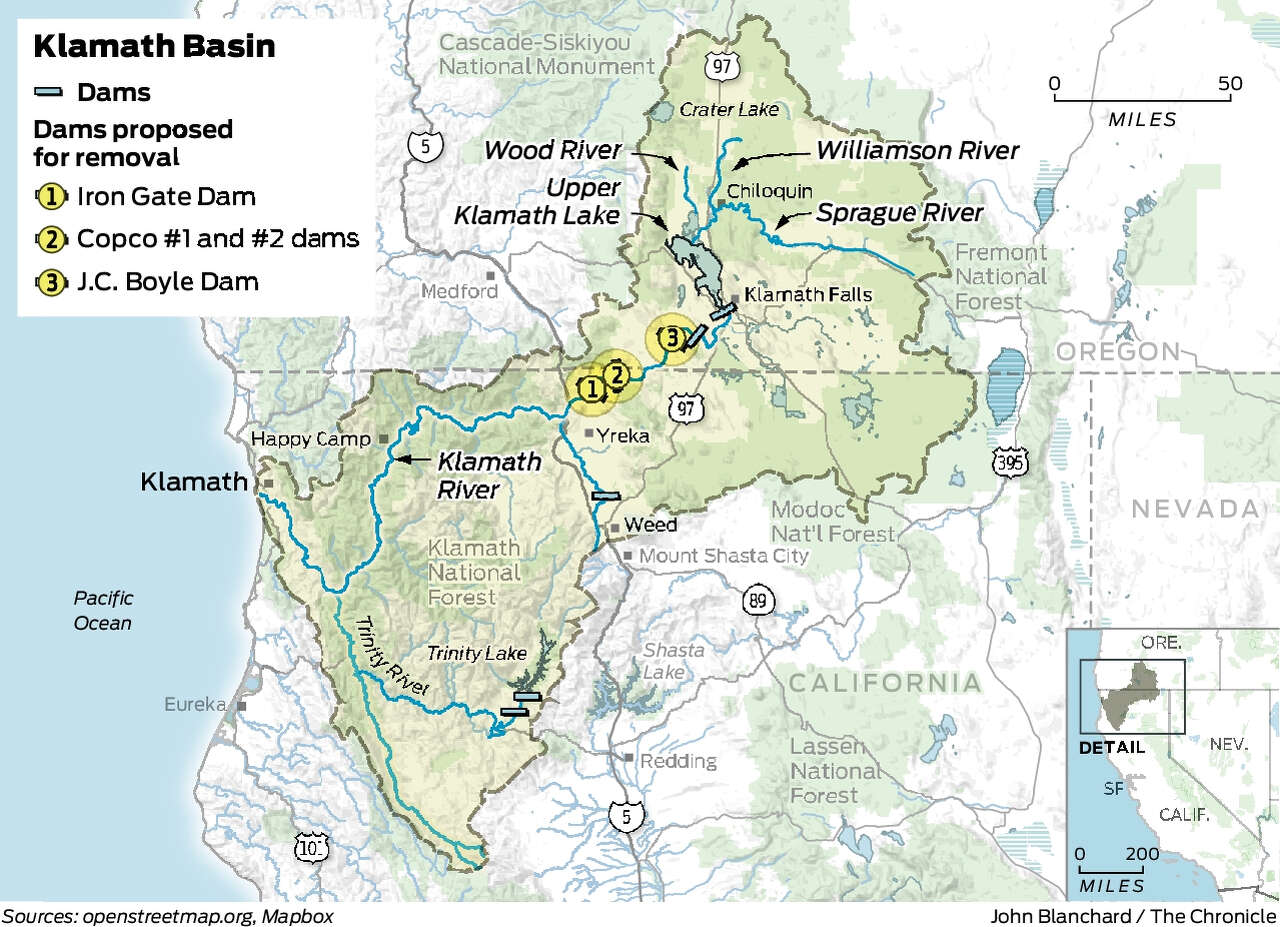

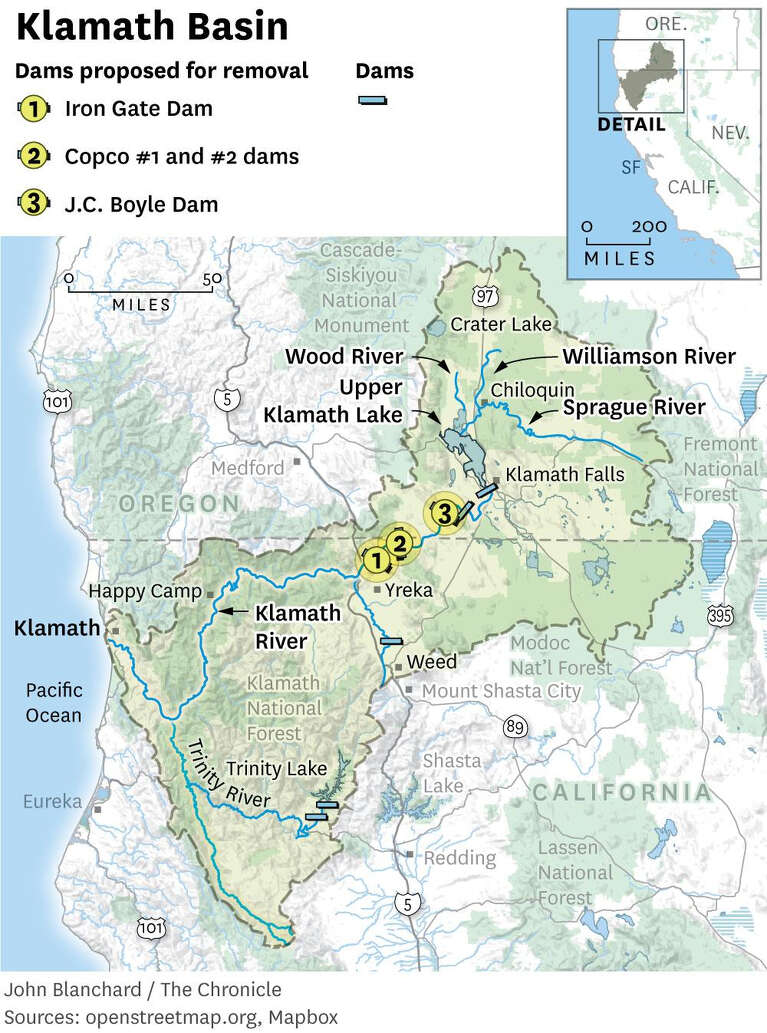

Santiago Mejia, Staff / The ChronicleThe Federal Energy Regulatory Commission voted Thursday to allow the license of four dams on the Klamath River to lapse, giving the final major go-ahead to the largest dam removal and river restoration project in the nation’s history.

The vote by federal regulators opens the door for the first of the four hydroelectric dams to come down next year in what has been a two-decade effort to liberate the once mighty river that spans southern Oregon and Northern California.

The goal of the nearly half-billion-dollar project is to restore the health of flora and fauna in the vast Klamath Basin, particularly salmon. The fish once numbered in the hundreds of thousands there and boasted the third largest salmon run in the continental U.S. Removing the dams from the 250-mile waterway will open fish passage, improve river flow and uproot toxic algal blooms.

The dam removal also represents a triumph for conservation groups, outdoorsmen and, perhaps most significantly, tribal groups, which have a long and tangled history tied to the forests and mountains of California’s far north and Oregon’s rural south.

Water pools behind the Copco dams on the Klamath River in Siskiyou County, as seen in May.

Santiago Mejia, Staff / The Chronicle“This isn’t just about the dams getting removed from the river, they’re getting removed from our culture and our way of life,” said Frankie Myers, vice chair of the Yurok Tribe, which has a reservation in Humboldt and Del Norte counties where the Klamath drains to the Pacific. “These dams have been black clouds hanging over our river and our people for 100 years.”

The Yurok Tribe is one of the affiliates of the Klamath River Renewal Corp., a nonprofit cooperative set up to take control of the facilities from power company PacifiCorp and manage the dam demolition. The power company, a subsidiary of Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway Energy, has decided the dams are too costly to operate.

Because dismantling the facilities involves hydroelectric infrastructure, FERC has been at the center of the campaign. Thursday’s move by the agency — approving the license surrender order for the power project — is FERC’s most decisive yet in a string of administrative actions. The approval essentially pulls the plug on energy operations.

“This project doesn’t happen if FERC doesn’t issue a surrender order,” said Mark Bransom, chief executive officer of the Klamath River Renewal Corp., which represents California and Oregon, tribal nations, water users, fishing groups and conservation organizations. “It’s a huge milestone for the project and for the parties that have been working on this for a couple of decades.”

While FERC is normally in the business of promoting power generation, not decommissioning it, the agency’s decision about the Klamath follows a push from an unlikely coalition of groups that advocated for the dam removal and came up with the money to fund it.

PacificCorp is contributing $200 million to the effort, with the agreement that it can unload the aging facilities without liability. Voter-approved water bonds in California are covering the rest.

“We have to understand this doesn’t happen every day,” FERC Chairman Richard Glick said at Thursday’s commission meeting in Washington, D.C. “This has been a long time coming, this order.”

The Iron Gate Dam on the Klamath River in Siskiyou County is one of four dams on the river scheduled for removal.

Santiago Mejia, Staff / The ChronicleThe dams no longer generate electricity. Nor are they, or the reservoirs above them, used for irrigation, municipal water supplies or flood control.

A handful of authorizations and permits still need to be granted before the dam removal can begin, but they’re mostly procedural.

With Thursday’s decision, the project remains on track for taking out the smallest of three California dams — the 33-foot-tall Copco No. 2 dam — as soon as next summer, Bransom said. The 173-foot Iron Gate Dam and 126-foot Copco No. 1 as well as Oregon’s J.C. Boyle dam will be razed the next year.

The J.C. Boyle Dam near Klamath Falls, Ore., shown in 2003, is a piece of PacifiCorp’s hydroelectric project on the Klamath River. It’s one of four dams scheduled for removal.

AP“Today’s action culminates more than a decade of work to revitalize the Klamath River and its vital role in the tribal communities, cultures and livelihoods sustained by it,” Gov. Gavin Newsom said in a statement. “California is grateful for the partnership of Oregon, the Yurok and Karuk tribes, Berkshire Hathaway and the many other stakeholders who came together to make this transformative effort a reality for the generations to come.”

The dam deconstruction will be followed by a massive seeding and planting effort that involves 97 species of native trees, brush and grasses, all of which once defined the landscape cut out by the river.

“这些都是我们必须采取的行动让我们back on track,” said Myers, with the Yurok Tribe. “Undoing those things that we knew were wrong. We can undo them. We can choose a different path.”

Kurtis Alexander is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: kalexander@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @kurtisalexander