This is a carousel. Use Next and Previous buttons to navigate

Anyone who walks west on Market Street in downtown San Francisco sees how abruptly - and unnervingly - a city can change.

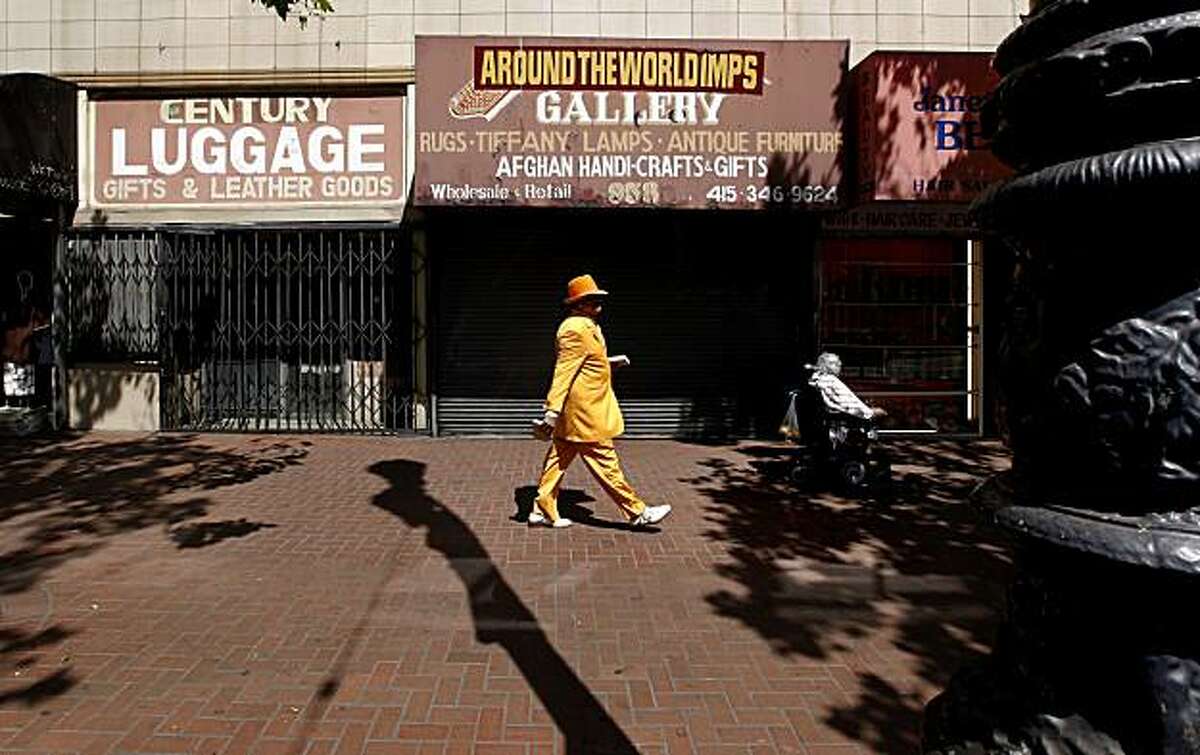

As soon as you cross Fifth Street, busy shops and a scattering of sidewalk cafes give way to empty storefronts and boarded-up buildings. There are men passed out on the grass in United Nations Plaza and men surveying the scene with cans of malt liquor in their hands. A huddle of chess-players punctuates their discussions with loud obscenities.

The scene can be forlorn at one moment, threatening the next, and it has persisted for more than four decades despite efforts by a procession of mayors including Gavin Newsom, who introduced his proposed budget last week from a storefront near Sixth and Mission streets to call attention to an area that he conceded "remains very challenging and vexing."

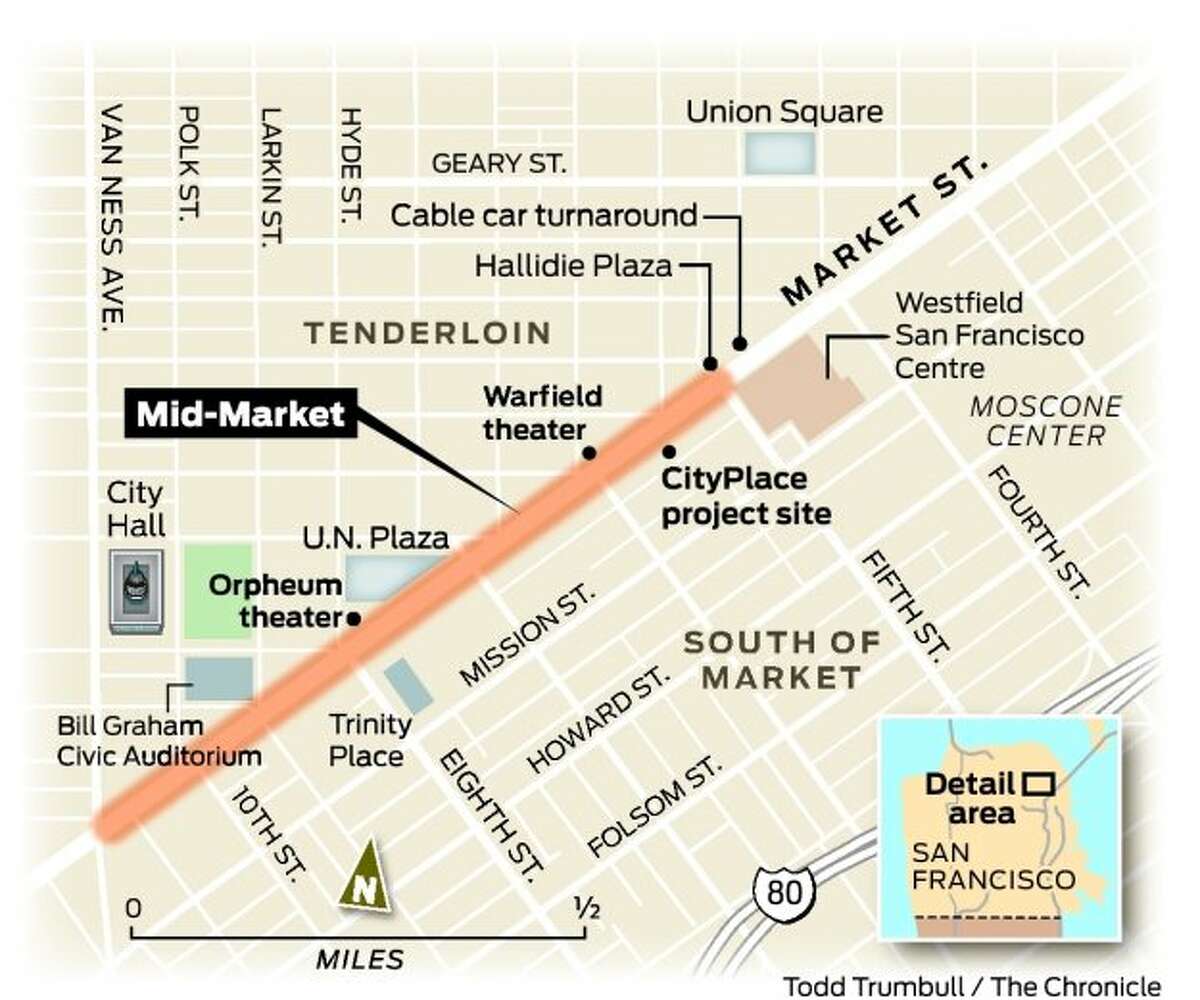

The question is whether new initiatives from City Hall will have a lasting impact - especially given the problems facing the blocks between Fifth and Van Ness, and the conflicting priorities of the groups that look on mid-Market as part of their turf.

"I've seen a lot of people come and go with big ideas about what they were going to do," says Carolyn Diamond, who has spent the last 25 years with the Market Street Association, a business advocacy group.

Gleaming, then grim

What makes the beleaguered state of mid-Market so baffling is that, logically, it should be where all strands of the city come together.

The 120-foot-wide pathway connects downtown's shopping and office districts to the government zone of Civic Center. Broadway shows can choose from two grand theaters on the strip, while a third hosts high-profile bands. There's a subway for BART and Muni, nine bus lines and a historic streetcar route that rivals the cablecarsas a tourist must-ride.

In its heyday, this stretch attracted people of all classes to the "settled progress" of what the 1939 Work Projects Administration guide to the city described as a "streamline array of neon signs, movie-theater marquees, neat awnings and gleaming glass."

But by 1962, Market Street had become a symbol not of progress but decay: "congested, dirty and unattractive" in the words of the ominously titled "What to Do About Market Street," a business-backed report that saw a thoroughfare in danger of deteriorating "past the point of no return."

That year is also when voters in Alameda, Contra Costa and San Francisco counties approved BART, a regional transit system that would require digging up Market to install subway lines. Soon, city leaders were touting the project as a way to redo Market Street - and voters in 1968 agreed to finance improvements that the argument in the ballot guide declared would bring "a magnificent boulevard ... a park-like environment for all San Franciscans - workers, shoppers and visitors."

BART service began in 1973. The new landscape with its 35-foot-wide sidewalks and procession of plazas was completed with fanfare in 1979.

Magnificence did not follow.

The brick sidewalks and granite paving of the 1968 vision remain in place, as do hundreds of sycamore trees and replicas of the ornate light poles installed along Market in 1916. But most of the customized design elements are long gone, including granite benches removed in the 1990s to discourage loitering. More recently, trees and shrubs were cleared from Hallidie Plaza to improve sight lines and make the busy space more secure.

Landscape in limbo

To be fair, much has changed. The blocks east of Fifth are a lively extension of the Union Square district, with shops and hotels along the way.

Mid-Market, though, remains sketchy at best.

Of the 88 storefronts between Fifth and Eighth streets, 31 are vacant. The occupied ones include smoke shops and a corner shop advertising "payday loans."

The broad sidewalks paired with blank storefronts create a void often filled by people who look not just out of luck, but on the prowl. Some spread battered goods for sale on the red bricks; others bide time between visits to the social services in the adjacent Tenderloin, or while relaxing after the free lunches served at several churches.

Nor is the atmosphere conducive to browsing - even though property owners began taxing themselves in 2007 to launch a "community benefits district" that augments city maintenance and provides uniformed "guides" to keep an eye out for trouble.

"The physical condition is better, the streets are cleaner," Diamond says. "Some days I walk (toward City Hall) and it feels pretty good. Other days, I'm scared to death."

Others take a more stark view.

"Mid-Market is in worse shape now than it was 10 years ago, with more disinvestment," says Amy Neches, deputy director of the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency. "If this isn't blight, I don't know what is."

Try, try again

The agency in March revived an effort to turn the strip into a redevelopment district. This would allow property taxes within the area to be directed toward such actions as the restoration of historic buildings for cultural use or subsidized housing.

Redevelopment is part of a larger mid-Market effort by City Hall that includes everything from art installations in vacant storefronts to a major repaving scheduled for 2013 that might be broadened to redesign the transit lanes and pedestrian landscape.

But redevelopment also demonstrates the difficulties of making major changes to a politically volatile terrain.

The original study began in 1995, with a 33-member advisory committee that eventually produced a planwith 76 objectives, many of them along the carefully vetted lines of "Develop a balanced mix of activities and businesses that serve the diversity of community residents, workers and visitors."

It was 2005 before city commissions gave their OK. The plan then went to the Board of Supervisors - and into limbo. Foes on the left equated it with gentrification, and no hearing was held.

This sort of standoff isn't new: a 1980s effort stalled after critics complained about building heights and that any improvements would drive out shops patronized by nearby low-income residents - an objection now moot.

"Activists have always been a major factor in preventing this area from rejuvenating itself," says Dean Macris, the city's planning director from 1981 to 1992 and 2004 to 2008. "If there was ever a reason to rethink it, this is the time."

The drawing board

即使没有再开发活动:切断al housing complexes have been approved, including a 400-foot housing tower at 10th and Market. Trinity Plaza at Eighth Street, a former motor lodge converted to housing in the 1970s, is being replaced by the 1,900-apartment Trinity Place.

Closer to Fifth Street, developer Urban Realty seeks approval for what it calls CityPlace - a five-story mall that would replace three buildings on the south side of the block and house discount retailers.

我大的问题解决方案s that surrounding development stalls until something is built.

The 10th and Market corner is an ugly pit of rubble. The segment of Trinity Place lining Market won't break ground for at least three years.

至于CityPlace,建筑将取代it vacant - and while there's support from business groups, the underground parking spaces included in the proposal are opposed by transit advocates who want to keep cars away from the area.

It's a variation of the debate that has occurred time and time again: Everyone agrees on the need for change, but some factions insist the cure is worse than the disease. If there's a difference this time, it's that improvements nearby have made mid-Market's void too grim to ignore.

"Market Street right now is a grand boulevard that turns into this strange wasteland," says Ed Reiskin, director of the city's Department of Public Works. "There's such a big problem, people have shied away. But the way to ensure that things不get better is to not even try."

The series

This is the start of an occasional series that looks at the challenges of redeveloping one of San Francisco's most beleaguered streets. Coming tomorrow is a look at MayorGavin Newsom'srole in pressing for a comeback.

A history of mid-Market Street

1962- As voters approve the Bay Area Rapid Transit district, San Francisco boosters sound the alarm about Market Street, BART's hub. "What was once San Francisco's pride has indisputably degenerated," frets a Chronicle editorial.

1963- Downtown design plan calls for closing Market Street to automobiles once BART goes in.

1966- Board of Supervisors votes to widen sidewalks from 22 to 35 feet, leaving four lanes of traffic.

1967——对巴特开始建设.

1968- Voters approve a bond to help fund $35 million in improvements along Market Street. The Examiner calls the vote essential to replace "a succession of schlock shops unmatched this side of New York's 42nd Street."

1969- The Board of Supervisors hears complaints about the state of the boulevard-to-be.

"We are going to have a street of excellence, charm and beauty which is going to attract people from all over the Bay Area and tourists from all over the country," one politician comments sympathetically. "It will also be an open invitation to every kind of crackpot and the eccentric behavior that these times have spawned."

1972- Supervisor RonaldPelosiproposes a redevelopment district along Market between Fifth and Eighth streets.

1973- Hallidie Plaza dedicated as BART finally opens, with Mayor Joseph Alioto praising its "artistic beauty."

1980- Two city commissions discuss closing the street to private cars from the Embarcadero to Eighth Street. The idea again founders. But another gains steam: keeping the streetcar line after all.

1982- Department of City Planning drafts a conservation and development study of mid-Market exploring how to improve the area without displacing residents.

1988- Workers begin ripping out old tracks and laying down new ones for the streetcar line, which will feature historic trains.

1988- San Francisco Centre opens at Fifth and Market with the posh Nordstrom department store as anchor. There's hope that upscale retail will continue to march west.

1995- The San Francisco Redevelopment Agency approves the creation of a "survey area" to explore revival of the blocks west of Fifth Street.

1996- Granite slab benches from the 1970s are removed between Sixth and Eighth streets after complaints about indigents who "drink cheap wine and then they hurl the bottles at passing cars or over their shoulders."

1997- Mayor Willie Brown suggests a car-free boulevard from Sixth Street east. Business protests stall the crusade.

2005——重建计划the works since 1995 is sent to the Board of Supervisors. They shelve it without comment.

2008- Supervisor Chris Daly's renewed call for a car-free zone - echoed by bicycling advocates - spawns a trial still under way: cars heading east must turn right at Tenth and Sixth streets, clearing room for buses and bicycles.

Blight stories

The blight associated with mid-Market might look perplexing, but there's a story behind every building. Here are five from a particularly grim stretch, the block between Sixth and Seventh streets on the south side of the street.

1019 Market:Built as the Eastern Outfitting department store in 1909, this is one of the few buildings that still has light industry on the upper floors.

1035 Market:Two buildings from 1933 were melded into one and housed long-gone Weinstein's department store. The new facade was added in a 2004 renovation; it has been mostly empty ever since.

1067 Market:Once the Egyptian Theater, since the 1970s this has been an adults-only outpost, one of the few that still remain in mid-Market.

1089 Market:For more than 50 years this was Merrill's Drugstore, patronized by nearby residents. Closed for more than five years.

1095 Market:The Grant Building from 1905 contains 140 offices, many of which in recent decades were leased by nonprofits. Now it's all but empty, and the owners hope to turn it into a boutique hotel for younger travelers.