It wasn’t the two hours that San Francisco firefighter Gerry Shannon spent working a chain saw under a collapsed Marina district building that got to him. It was the five minutes he spent lying there while a colleague replaced his blade.

Shannon was on his back in the claustrophobic crawl space, no more than 2 feet high. He could see the glow of approaching fire. He pictured the fire chief ringing the doorbell of his home to inform his wife, Deidre, that her husband had died while trying to rescue a woman trapped in her apartment after the Loma Prieta earthquake. He pictured Deidre giving the news to their three kids.

“Those five minutes changed my thinking,” Shannon, 74, says now in a voice becalmed by his daily 40 minutes of meditation. “They talk about time standing still. It did.”

It is a common story among people who have faced a life-threatening situation — the promise that if they survive, they will mend their ways and stop wasting time or taking life and family for granted. These vows are often forgotten as soon as the danger is lifted, and Shannon was tempted to go back to his life in the Irish bars of the Sunset District, where he grew up.

He was now a hero with a rescue story that had spread nationwide. He had earned the San Francisco Fire Department’s highest medal for valor. Drinks would be on the house for a long time.

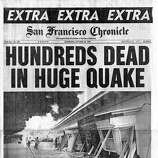

But he never went back on the vow to pursue enlightenment that he made under that building the evening of Oct. 17, 1989. He has spent 30 years on a spiritual quest that has taken the fourth-generation city boy out of his element and out of the country.

“It was a life-changing day,” he says, “and I survived it.”

When the TV news helicopters showed flames shooting up from fires all over the Marina after the quake, Shannon’s son Casey, 9, asked his mother, “Do you think dad’s there?” She replied, “Yes,” then added, “but he won’t take any chances.”

At that moment, Shannon was taking more chances than he ever had. A four-story apartment building at Beach and Divisadero streets had collapsed, its upper stories fallen forward onto the street and its lower floors pancaked to the ground.

Sherra Cox, 56, an office manager, had come home from work early to watch the Giants and A’s in the World Series. Her building was two blocks from the bay and built on landfill. When the 6.9 earthquake hit at 5:04 p.m., the structure lurched forward off of its foundation and onto the street.

The apartment house next to hers erupted in flames that threatened to spread. The smell of gas was everywhere, and Cox was now trapped beneath heavy beams in the wreckage of her second-floor corner unit.

She managed to work one arm free, grabbed a loose pipe and banged it on the metal post of her bed. A paramedic heard it and alerted the nearest firefighter at hand, who happened to be Shannon, a 20-year veteran who had been detailed to the scene from his station on Jerrold Avenue near Candlestick Park.

When a building collapsed on Cervantes Boulevard in the Marina, Shannon’s crew of five had been ordered all the way to Divisadero Street. He thought they were sent just as backup. When he got to the top of the hill looking north, the Marina “looked like a bomb had gone off,” he says.

Firefighter Gerry Shannon helped in Marina rescue efforts

Media: San Francisco ChronicleThe building was compressed against the ground, so the only way to reach Cox was to go underneath and cut a path through the floor joists. Shannon got a chain saw from the engine and went to work in the crawl space, so tight he had to take his helmet off to fit. It was slow going. It took him 2½ hours and two saw blades to go 35 feet.

但他要考克斯,他打破了她的臀部和图像的基本单位vis. By then water was coming into the building from hoses dousing the fire next door. Shannon took off his heavy coat and put it over Cox. She grabbed his hand to make sure he wouldn’t leave her, but he had to go get a new saw blade.

“I said, ‘I’ll be back, I promise you,’” he recalls. “I don’t think she believed me.” But she finally let go of his hand, and he did come back, 10 minutes later, with a fresh blade to free her from the beam pinning her to the floor.

He crawled back out again, far enough to call for a stretcher board, which paramedic Rich Allen pushed through. He checked Cox’s vitals before they put her on the board and pushed her back out the way he had come. The crowd cheered as she was loaded into an ambulance, but she would not let it pull away until she got the last name of the firefighter who rescued her.

“The efforts he went to to save a complete stranger,” Cox later told The Chronicle. “He is the story, I just happen to be the end of it.”

Shannon never wanted to be the story. He was embarrassed by the attention, even when he was among a dozen heroes to throw out the ceremonial first pitch when the World Series resumed at Candlestick.

“I was just a mediocre fireman who was in the wrong place at the right time,” he says. “You wait your whole career for something like that, and then when it shows up, you don’t know how you are going to handle it.”

The first sign that he had changed came when he arrived at San Francisco General Hospital the next day with flowers for Cox.

“Usually, you don’t even call, because if they died it ruins the whole effect,” he says. “But with her it was different.” He kept coming back. When Christmas came around he brought his wife and kids and a tree to brighten Cox’s hospital room.

The bond they’d formed over those two hours in her collapsed apartment building was stronger than Shannon anticipated. Cox persuaded him to do something he hadn’t done since he was a freshman at Riordan High School — read a book. He’d been kicked out of Riordan for fighting, then out of Lincoln High School for the same reason. He’d had to finish at a continuation school.

During Shannon’s hospital visits, Cox started talking about Eastern religion and philosophy and lending him books. He eventually moved on to the Greek philosophers, Plato and Aristotle. He and Cox would pass books on Buddhism back and forth.

After she was released to start five months of rehab, he visited and encouraged her to walk. She held his arm with one hand and her walker with the other. When Shannon learned that she didn’t have a place to go for Thanksgiving, he invited her to spend it with his family.

Cox was a pianist who had played rehearsals for the San Francisco Symphony and Opera. Six months after her release, she and Shannon attended the Opera together. When her health later failed and she was using a wheelchair, Shannon would take her to lunch at Westlake Joe’s. She’d have a martini. By then Shannon wasn’t drinking at all.

“It didn’t work anymore for me,” he says. “It wasn’t part of my lifestyle.”

He’d quit his side job as a bouncer and bartender and stopped playing softball, with its long hours of postgame drinking. His wife, Deidre, had been after him to move from their flat in the Sunset to Marin County, so they did, first to San Rafael then to Novato.

The 2½ hours he spent under that building in the Marina and the months he spent with Cox afterward had altered his outlook.

“I just wanted to do more with my life besides sitting at a bar watching the Miller Hi-Life sign blink on and off,” he says.

The hours he used to spend in bars were now spent at Spirit Rock, a meditation center in West Marin. That led to a pilgrimage to Thailand, searching for the monastery of one of the monks he’d studied with. When he returned, he took up silent retreats, sitting for 10 days “without moving, looking up or talking” in the Mojave Desert. He has been to Nepal and Tibet and sat with the Dalai Lama for 10 days in India.

He sectioned off part of his home for meditation, which he practices for 40 minutes every night at 9 p.m. For years he meditated while wearing a ceremonial shawl and sitting on pillows, with incense burning. But now that he’s older, he sits in a chair.

“Buddhism is a philosophy, not a religion,” he says. “I steer clear of organized religion.”

Shannon has not had a drink in 19 years, though he still plays golf every Monday with his drinking buddies from Riordan, who also became firefighters. His other link to his old San Francisco life was Cox, who had moved to an apartment on Nob Hill.

But she missed the Marina, so Shannon helped her find a corner unit in an apartment building there just like her old one. When he took her there to see it, she halted suddenly at the front door.

“She said, ‘I’m sorry you went to all of this trouble, but I just can’t go in there,’” he says. “I looked at her face and it had all come back to her.”

So he found her another place at Lake Merced.

香农成为考克斯的医学守护她through a series of amputations, a result of gangrene that had formed when her circulation had been cut off while trapped. She decided to put an end to the operations in summer 2009, and died about a month later.

When Shannon visited her for the last time, he broke down in tears. He still becomes emotional talking about her now.

“She said, ‘What are you upset about? These last 20 years were on the house.’”

It’s now been 30 years on the house for Shannon. For his heroics in rescuing Cox, he was issued the Scannell Medal, the San Francisco Fire Department’s highest honor. He was named Fireman of the Year by Firehouse magazine. The manufacturers of Kleenex flew him to Washington to accept a “God Bless You” Award.

He was promoted to lieutenant in 1995 and captain in 2000. In 2003, he retired after 33 years with the department. The helmet he was wearing on the day of the earthquake and his framed medals are kept in his bedroom. It takes a lot of prodding to get him to bring them out.

“It’s kind of an ego thing I try to avoid,” he says. As a Buddhist, he says, he is dedicated to the present, not the past.

“I haven’t thought about the earthquake in a long time, even when it comes up on the anniversary,” he says. “Thirty years ago, who remembers that?”

Sam Whiting is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email:swhiting@sfchronicle.comTwitter:@SamWhitingSF