This is a carousel. Use Next and Previous buttons to navigate

Theprevious two Portalsdescribed how students protesting the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings in San Francisco in May 1960 were blasted with fire hoses, beaten and dragged down the stairs of City Hall by police.

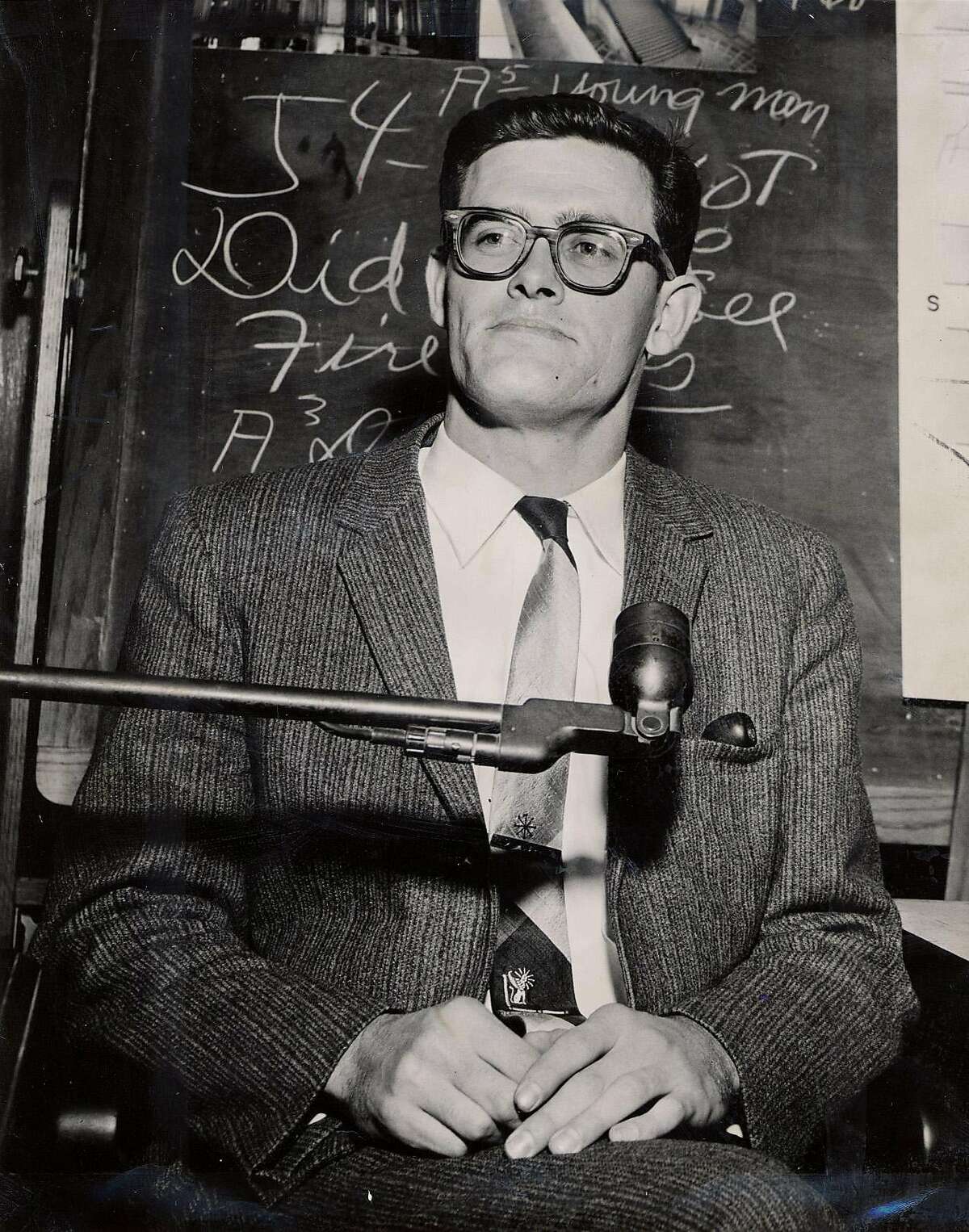

All 68 protesters arrested had their charges quickly dismissed, with one exception: 22-year-old Robert Meisenbach, a UC Berkeley English major who was accused of provoking the confrontation by attacking a police officer and was charged with felony assault. That charge was largely supported by a story written by star San Francisco Examiner reporter Ed Montgomery, which said Meisenbach had clubbed the officer with a baton.

The prosecution would come to regret hanging its case on Montgomery’s reporting.

As Seth Rosenfeld writes in “Subversives: The FBI’s War on Student Radicals, and Reagan’s Rise to Power,” FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover called the protests “the most successful communist coup to occur in the San Francisco area in 25 years.” He ordered the special agent in charge of the FBI’s San Francisco field office, Richard Auerbach, to prepare a report on the Communist Party’s involvement in the protests.

Auerbach’s agents hastily put together “Project: Revolution in San Francisco.” Its predetermined finding: Communists had manipulated students into engaging in “wild rioting and disorder” that threatened “the government of the city of San Francisco and defied the authority and power of the federal government.”

Hoover used the report as the basis for a booklet, “Communist Target — Youth: Communist Infiltration and Agitation Tactics.” The 18-page booklet, signed by Hoover and released to news outlets across the country, said Communists had orchestrated the protests and used “mob psychology” to incite the students, who were portrayed as gullible dupes of the wily reds.

“Communist Target — Youth” resulted in alarmist coverage in the New York Times and other leading newspapers. At the same time, HUAC released its own propaganda screed against the students, a 42-minute documentary titled “Operation Abolition.” The film, which can be seen online, features grainy footage of the protests while an authoritative-sounding male narrator declaims that “Operation Abolition” was the name the Communists gave their plot to destroy HUAC, weaken the FBI and “discredit its great director, J, Edgar Hoover.”

The film got enormous play. The Defense Department used it in mandatory training and planned to show it to 500,000 soldiers. Schools, colleges, churches and police departments across the country screened it, as did companies like Standard Oil, Pacific Gas and Electric Co., and Pacific Telephone and Telegraph.

But criticism of “Operation Abolition” was immediate. Students who had been at the protests denounced it as distorted and biased, and a law professor commissioned by UC Berkeley Chancellor Clark Kerr concluded that the students’ criticisms were legitimate. The film became a cult classic at Cal, where it was seen as proof that the government would lie about students who were exercising their constitutional rights. Chronicle columnist Herb Caen blasted the film, and the Washington Post editorialized that the movie “warps the truth.”

Alarmed, Hoover asked Auerbach to vet the film. Auerbach discovered that there were even more errors than the Post had uncovered. Most important, there was no evidence that anyone had leaped over a barricade or beaten a police officer, as the film asserted.

Hoover began dodging questions about the accuracy of “Operation Abolition,” but he kept promoting “Communist Target — Youth.” By the time of Meisenbach’s trial, more than 300,000 copies of the pamphlet had been distributed.

The trial opened April 18, 1961, in the old Hall of Justice on Kearny Street. The stress of awaiting trial on charges that could jail Meisenbach for 10 years had given the young man ulcers, made his hands tremble and led him to consider suicide. But he refused a plea bargain that would have let him walk free, saying he believed in his innocence and in the truth.

The prosecutor, Walter Giubbini, opened by asserting that Meisenbach had attacked a police officer, Ralph Schlaumleffel. One of Meisenbach’s attorneys, Jack Berman, called the charges “a fabric of lies.” He said Meisenbach came from a respected Central Valley family, was not an activist, had attended the hearings mostly out of curiosity and had been photographed at the time of the alleged assault 40 feet away.

Giubbini called Schlaumleffel, who asserted that Meisenbach had hit him with his own baton. On cross-examination, however, the patrolman said Meisenbach’s alleged assault had happened after the fire hoses were turned on, not before. This undermined Hoover’s and the prosecution’s central claim — that Meisenbach had touched off the melee.

After a series of defense witnesses testified that they hadn’t seen any violence by students before the police turned the fire hoses on them, famed defense attorney Charles Garry called Meisenbach. Speaking in such a low voice he could barely be heard, the Marine veteran said he had been standing by a pillar when the fire hoses were turned on. He was trying to leave when he was beaten by police officers, he said.

Garry asked Meisenbach if there was anything else he wanted to say. Meisenbach started to weep. “I was beaten and I was afraid,” he said. Then, in a whisper, he said, “I had an involuntary bowel movement.”

控方称两名officers, who testified that they hadn’t seen any officers beating Meisenbach. Under cross-examination, they also said they hadn’t seen Meisenbach strike Schlaumleffel.

It took the jury less than three hours to return a verdict of not guilty. Hoover ordered his aides not to comment on the verdict and to stop distributing “Communist Target — Youth.”

The prosecution’s star witness, Examiner reporter Montgomery, never testified. The reason was that before the trial, the newsman told Giubbini that the story he had written reporting that Meisenbach had hit Schlaumleffel was false. Montgomery, a longtime water carrier for the FBI, had published it anyway.

The City Hall debacle was a black eye for Hoover, for HUAC and for their shrill, paranoid worldview. HUAC never returned to San Francisco. And a student protest movement that would shake America had been baptized by the fire hoses of the SFPD.

Gary Kamiya is the author of the best-selling book “Cool Gray City of Love: 49 Views of San Francisco,” awarded the Northern California Book Award in creative nonfiction. All the material in Portals of the Past is original for The San Francisco Chronicle. Email:metro@sfchronicle.com

Trivia time

Previous trivia question:When did the first Pony Express rider arrive in San Francisco, and how long did the trip from St. Joseph, Mo., take?

Answer:April 14, 1860. The trip took 10 days.

This week’s trivia question:Prefabricated metal houses were popular in the 1850s. Why did they fall from favor?

Editor’s note